Periods of “humming” and “babbling” and their stimulation article on the topic

The period of “humbling” and its stimulation in children

Humming is the melodious pronunciation of chains of vowel sounds close to [a, y, y], often in combination with consonant-like sounds [g, m]. According to similar humming sounds, they are of laryngeal-pharyngeal-posterior lingual origin, which is reflected in the terms “humming,” “cooing,” and “humming.” The vowel-like sounds of hum are closest to the neutral e, a sound in which the tongue occupies a mid-position in the mouth. Consonant-like elements are usually palatalized, that is, they sound soft.

The sounds of humming, in contrast to screaming and crying, always arise against the background of an emotionally positive state, comfort and are not associated with organic needs. Humming is a kind of “play” of the organs of the articulatory apparatus, necessary for its development. Up to 3 months voice activity does not depend on the operation of the auditory analyzer. After 3 months pronunciation is carried out under the control of hearing. The child shows interest in his own vocalizations, listening and repeating them (the phenomenon of autoecholalia) (Mikirtumov B.E., Koshchavtsev A.G., Grechany S.V., 2001).

Thanks to the vocal reactions of humming, which gradually acquire different intonation colors, the child learns the intonation system of the language and copies the intonations of the people around him. Booming is a consequence of randomly occurring positions of the future articulatory apparatus - lips, tongue, soft palate, pharynx and larynx. Walking promotes the development of a child’s auditory attention and articulatory apparatus (Sobotovich E.F., 2003).

It is the same for children all over the world. The appearance of humming coincides with the appearance of a “revival complex” in the baby: moderately pronounced movements of the limbs, turns of the head, gaze movements, smiles and vocalizations addressed to the mother. All components of the revitalization complex are inseparable from each other, syncretic: a child in the first months of life cannot make sounds outside of general motor activity, just as he cannot move his arms and legs, remaining silent. It is also observed in deaf infants who did not have sound contact with their mother (Shokhor-Trotskaya M.K., 2006). Humming, just like screaming, is the result of the activity of the subcortical structures of the brain, i.e. the humming is involuntary (Vizel T.G., 2005; Vinarskaya E.N., 1987). Gradually, the baby establishes a connection between the melodious components of the cry (they will later be designated “humming”) and the mother’s behavior in the form of an emotional relationship with the child. At 2-3 months, the child’s need for such communication greatly increases.

Each of the humming sounds, which is the result of a complex synergy, can be stereotypically reproduced repeatedly through the mechanism of tactile-kinesthetic feedback. In the first autoecholalic phase of this period, auditory copies of tactile-kinesthetic images of humming are created, which make possible the transition to the second onomatopoeic phase. In this phase, universal emotional and expressive vowel timbres, characteristic of all children (without differences in their national and cultural background), receive nationally specific polishing, and those whose equivalents are absent in maternal speech are inhibited. Thus, sound complexes of humming, carried out while inhaling, are inhibited without receiving reinforcement. The transition to the second phase of humming is possible only in children with intact hearing.

The blossoming of the buzz falls at 4-6 months of life. Apparently, by this time the child has fully mastered the national specifics of the emotional and expressive vocalism of his native speech, which explains the following amazing fact: adult Americans, Danes and Chinese can recognize their compatriots among 6-month-old babies by the humming sounds they make.

When perceiving the mother’s speech, the child perceives only her vocalized parts, and he ignores everything that is between them. The period of humming ends with the child, on the verge of the first half of the year, beginning to recognize specific vowel timbres from unstressed syllables in which they are merged with the noise elements of the syllable. The transition to the perception of “difficult” noisy areas of maternal speech is associated with an increase in communicative-cognitive motivation.

Acquiring a nationally specific form, the child’s sound reactions acquire a sign function during the humming period. The vocal components of these reactions signify the functional states experienced by the child. Based on the vocal components of the mother’s statements, the child makes unconscious assessments of her functional states and, in accordance with these assessments, also unconsciously builds his adaptive behavior: either reaches out to her and imitates her, or turns away and shows aggressive reactions towards her.

Silent adults or adults with emotionally inexpressive vocal components of speech may not evoke indicative-exploratory behavior in a child during the booming period, and, consequently, communicative-cognitive activity.

While babbling (and at first without babbling), the child lets out bubbles of saliva. This reaction indicates the formation of differentiated innervation of the lips (Sapogova E.E., 2001). Low buzzing activity inhibits the development of speech motor and speech auditory analyzers (Arkhipova E.F., 1989).

During the humming period, the sound side of children's speech is devoid of four important features inherent in speech sounds: a) correlation; b) “fixed” localization (“stable” articulation); c) constancy of articulatory positions (there is a large and largely random “scatter” of articulations); d) relevance, i.e. the correspondence of these articulations to the orthoepic (phonetic) norms of the native language (Glukhov V.P., 2005).

The appearance of humming in the 2-3rd month, associated with the development of vocalized exhalation in the child, occurs as a certain motor base for training speech breathing is formed (holding the head, turning on the side, etc.).

Signs of speech dysontogenesis at the stage of humming

• The appearance of hooting (stages before hooting) at 3-5 months may be a sign of cerebral palsy (E.F. Arkhipova, 1989).

• Booming does not occur in response to emotional communication with an adult.

• Humming, more like a squeal.

• Absence of the second phase of humming: imitation of sounds (assessed from 4 months).

• The humming of the blind is no different from the humming of the sighted, although some blind people experience a longer period of humming.

• Humming sounds without melodiousness, short sounds.

• Absence of back-lingual sounds in humming (a sign of excessive tension in the root of the tongue).

• Low buzzing activity.

There is no need to communicate with your child too loudly or too quietly. The ear shows maximum sensitivity to sounds of medium volume.

The baby smiles, makes sounds of satisfaction if the adult speaks in a friendly, affectionate tone, and, on the contrary, screams if the adult is angry and there is an angry, irritated, dissatisfied intonation in his voice. The child does not yet understand the meaning of the speech addressed to him, but is sensitive to intonation. Children look intently at the face of the person speaking. If at these moments the adult’s facial expressions and intonation are joyful, then children clearly repeat facial movements (echopraxia) and imitate vocal reactions (echolalia) (Belyakova L.I., Dyakova E.A., 1998).

To develop the skills of walking, teachers recommend to parents the so-called “visual communication”, during which the child peers at the adult’s facial expressions and tries to reproduce them. In most cases, at the first manifestations of humming, his parents begin to talk to the baby. The child picks up the sounds he hears from the speech of adults and repeats them. In turn, the adult repeats the child’s “speech” reactions. Such mutual imitation contributes to the rapid development of increasingly complex pre-speech reactions of the child. Pre-speech reactions, as a rule, do not develop well enough in cases where, although the child is being trained, he cannot hear himself or the adult. For example, if there is loud music in the room, adults are talking to each other, or other children are making noise, the child will very soon fall silent.

There is another important condition for the normal development of pre-speech reactions: the child must clearly see the face of an adult, the movements of the organs of articulation of the person talking to him that are accessible to perception (Glukhov V.P., 2005).

With the youngest children, who have no humming or very little activity, the work consists of providing him with samples of full-fledged humming to listen to. They can come from nearby children whose humming is active; Tape recordings of humming can be used, as well as imitation of it by adults, as if playing with children: “gu-agu-gu-agu-gu”... These measures are designed to evoke an early imitative reflex. The need for this from a neuropsychological position is that at a later age the brain structures responsible for the imitative reflex become inert: they are very difficult, if not impossible, to include in the work (Wiesel T.G., 2005).

Gushing in a child is caused by a gentle voice or singing. First, the child is given the opportunity to listen to the soft, pleasant sounds of the voice. Then the adult slowly pronounces the sounds a, agy, gu, etc., opening his mouth wide so that the child can see the adult’s articulation. If the child does not repeat these movements after the adult, then they passively develop an imitative reaction. Lightly stroking the child's lips, the child's mouth is opened in a certain rhythm at the moment the adult pronounces a sound.

Reception 1: repeat 4-6 times during the day (Arkhipova E.F., 1989). When stimulating humming, it is necessary to achieve spontaneous, involuntary vocalization. For this purpose, a manual vibration massage of the chest, larynx, and under the lower jaw is performed, which stimulates proprioceptive sensations, distracting the child from the act of phonation. This promotes spontaneous evocation of the voice, since during the massage the adult utters melodious humming sounds.

Reception 2: repeated 1-2 times a day. For example, the oral area is massaged to the accompaniment of calm music. To the accompaniment of rhythmic music, manipulative-objective actions are taught, for example: knocking with a rattle, clapping your hands. Music classes are held 1-2 times a week.

While talking to the baby, tickle him and stroke him. Your speech and your smile, combined with tactile-motor stimulation, will help your baby smile at you. In addition, such “inhibition” stimulates the revitalization complex.

The period of babbling. Stimulation of its development

Appears at the age of 5-6 months. and is a combination of consonants and vowels. The transition to babbling is associated with the development of rhythm and consistency of breathing and movements of the articulatory apparatus. In the middle of the first year of life, the striatal subcortical nuclei mature and the child’s motivational sphere becomes more complex. The functioning of the striatal nuclei begins gradually, which is revealed in the appearance of such emotional expressive reactions as laughter and crying (Vinarskaya E.N., 1987). With its appearance, we can talk about the beginning of the syntagmatic organization of speech - the combination of individual articulations into a linear sequence with modulation in timbre and pitch.

At first, the babbling is spontaneous. The child listens to the sounds he pronounces and tries to reproduce them. The appearance of echolalia (imitation onomatopoeia) leads to a rapid increase in the number of syllables and sounds used. The process is active: the baby looks at the adult, follows the movement of his lips and repeats what he hears.

An important role is played by the ability to control the articulatory apparatus based on visual and auditory perception. By the 8th month, the sound composition becomes more complex with the sound combinations “te-te-te”, “ta-ta-ta”, “tla”, “dla”, etc. The vowel “i” is used more often. “o” appears as an independent sound (Mikirtumov B.E., Koshchavtsev A.G., Grechany S.V., 2001).

The babbling begins to resemble a song. The ability to connect different syllables appears (the stage of verbal babble).

Studies of the sound composition of babble have made it possible to establish a number of its regularities:

1) the presence in babble of most of the sounds that are unusual for the Russian language;

2) diversity and fine differentiation;

3) replacing hard-to-pronounce sounds with similar ones in articulation;

4) the dependence of pronunciation mastery on the primary development of the vocal apparatus;

5) the dependence of the sequence of appearance of sounds on the complexity of their pronunciation.

Of the great variety of innate babbling synergies, only those that are systematically reinforced by external sound complexes remain in the child’s everyday life (Vinarskaya E.N., 1987).

At the 9th month, babbling becomes precise and differentiated. It is possible to pronounce the combinations “ma-ma”, “ba-ba” without communicating with certain people (two-syllable babble).

Increased accentuation of maternal speech addressed to the child, with an abundance of emotionally emphasized stressed syllables (Sasha, my dear), as well as episodes of passionate rhythmic appeals of a nursing mother to the baby “Butsiki, Mutsiki, Dutsiki” or “ shirt, shonka, shonka"), during which the mother caresses and kisses him, lead to the fact that stressed syllables, together with their noisy pre-stressed and post-stressed “neighbors,” receive in the mother’s speech a single sound of changing sonority: now increasing, now falling. Feeling these effects of sonority, the child imitatively reproduces them in his babbling reactions and thus begins to operationally master the sound structure of integral pseudowords, which in maternal speech are no longer correlated with syllables, but with parts of phonetic words, phonetic words and their combinations (Vinarskaya E.N. , 1987).

Observations show that the initial babbling chains of stereotypical vocalizations (a-a-a, etc.) are replaced at 8-10 months. chains of stereotypical segments with a noise beginning (cha-cha-cha, etc.); then at 9-10 months. chains of segments appear with a stereotypical noise beginning, but with an already changing vocal end (tyo-tya-te, etc.) and, finally, at 10-12 months. chains of segments with changing noise beginnings appear (wa-la, ma-la, da-la; pa-na, pa-pa-na, a-ma-na, ba-ba-na, etc.).

Length of babbling chains at the age of 8 months. is maximum and averages 4-5 segments, although in some cases it can reach 12 segments. Then the average number of chain segments begins to fall and by 13-16 months it is 2.5 segments, which is close to the average number of syllables in word forms of Russian speech - 2.3.

The sound composition of babble is the result of kinesthetic “tuning” of the articulatory apparatus according to the auditory, acoustic imitation of the speech of others (Shokhor-Trotskaya M.K., 2006).

Children who are deaf from birth do not develop either self-imitation or imitation of the speech of others. The early babbling that appears in them, without receiving reinforcement from auditory perception, gradually fades away (Neiman L.V., Bogomilsky M.R., 2001).

The sequence of mastering the sounds of babbling is determined by the patterns of development of the speech motor analyzer: coarse articulatory differentiations are replaced by increasingly subtle ones, and easy articulatory patterns give way to difficult ones (Arkhipova E.F., 1989).

The most intense process of accumulation of babbling sounds occurs after the sixth month during the seventh month, then the process of accumulation of sounds slows down and few new sounds appear. The process of intensive accumulation of sounds in babbling coincides with the period of myelination, the significance of which lies in the fact that its onset is associated with a transition from generalized movements to more differentiated ones (N.A. Bernstein). From 7-8 months to one year, articulation does not expand particularly, but speech understanding appears. During this period, semantic load is received not by phonemes, but by intonation, rhythm, and then the general contour of the word (Arkhipova E.F., 2007).

By 10 months, a higher level of communicative and cognitive activity is formed. All this stimulates a leap in the child’s motivational sphere. Carrying out emotional interaction with the child, the mother systematically turns her attention to various objects of the surrounding reality and thereby highlights them with her voice and her emotions. The child assimilates these “emotional labels” of objects along with the corresponding sound images. Imitating his mother and using the chains of babbling segments already available to him, he reproduces the first babbling words, the form increasingly approaching the sound form of the words of his native language (Arkhipova E.F., 2007).

The period of babbling coincides with the formation of the child’s sitting function. Initially, the child tries to sit down. Gradually, his ability to hold his torso in a sitting position increases, which is usually fully formed by six months of life (Belyakova L.I., Dyakova E.A., 1998). The vocal stream, characteristic of humming, begins to break up into syllables, and the psychophysiological mechanism of syllable formation is gradually formed.

Babbling speech, being rhythmically organized, is closely related to the rhythmic movements of the child, the need for which appears by 5-6 months of life. Waving his arms or jumping in the arms of adults, he rhythmically repeats the syllables “ta-ta-ta,” “ha-ga-ha,” etc. for several minutes in a row. This rhythm represents the archaic phase of language, which explains its early appearance in speech ontogenesis. Therefore, it is very important to give the child freedom of movement, which affects not only the development of his psychomotor skills, but also the formation of speech articulations.

After 8 months, sounds that do not correspond to the phonetic system of the native language gradually begin to fade away.

By about 11 months, chains with a changing noise onset appear (va - la, di - ka, dya - na, ba - na - pa, e - ma - va, etc.). In this case, any one syllable is distinguished by its duration, volume, and pitch. Most likely, this is how stress is laid down in pre-speech means of communication (N.I. Zhinkin).

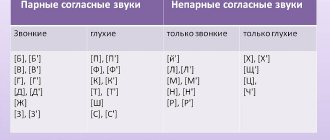

IN AND. Beltyukov identified the sequence of appearance of consonant sounds in babbling according to the principle of reducing the contrast of a group of consonant sounds when they appear in babbling: oral and nasal, voiced and voiceless, hard and soft (forelingual), lingual (stop and fricative).

Some babbling sounds that do not correspond to the phonemes of the speech heard by the child are lost, and new speech sounds similar to the phonemes of the speech environment appear.

There is also a third stage in the development of babbling, during which the child begins to pronounce “words” formed by repeating the same syllable like: “baba”, “ma-ma”. In attempts at verbal communication, children at 10-12 months of age already reproduce the most typical characteristics of the rhythm of their native language. The temporal organization of such pre-speech vocalizations contains elements similar to the rhythmic structuring of adult speech. Such “words,” as a rule, do not correspond to a real object, although the child pronounces them quite clearly. This stage of babbling is usually short, and the baby soon begins to speak his first words.

Stages of development of babbling (according to V.I. Beltyukov):

Stage 1 - a hereditary program of voiced articulatory movements, implemented regardless of the hearing of children and the speech of others;

Stage 2 – formation of the autoecholalia mechanism;

Stage 3 – the appearance of combinations of sound-syllable complexes, physiological echolalia and the transition to active speech

Pronouncing these sounds is pleasant for the child, so his babbling sometimes continues throughout his waking hours (Mukhina V.S., 1999).

Oddly enough, the quality and activity of babbling are largely related to how the child is fed, namely, whether full sucking movements are performed in acts of feeding, or whether they are in the right volume. Artificial children, of whom the majority are now suckling, often lack such action: the lips and tongue do not gain sufficient strength, and most importantly, mobility and differentiated (the ability to act in different parts separately). This can play a negative role in speech development. If natural feeding is not possible, then spoons with small holes are needed. A child must work to get food until there are beads of sweat on his forehead. Children whose tongue muscles have gained sufficient strength and mobility love to play with it. They stick it out, lick their lips, chew it with toothless gums, turn it to one side and in different directions (Wiesel T.G., 2005).

Babbling is necessary to train the connections between pronunciation and hearing in order to develop auditory control over the pronunciation of sounds (Isenina E.I., 1999). An infant is capable of perceiving a smile, gesture, or word only addressed to him personally. Only to them does he react with appropriate animation, a smile, and sound (Tikheeva E.I., 1981).

Signs of dysontogenesis babble

• Late onset of babbling (after 6 months) (the appearance of babbling after 8 months is one of the signs of intellectual disability, cerebral palsy);

• Absence of babbling or any of its stages.

• Poverty of the sound content of babbling (limiting it to the sounds: ma, pa, ea, ae).

• Absence of syllable sequences in babbling: only individual syllables are represented.

• Absence of autoecholalia and echolalia mechanisms in babbling.

• Absence of labiodental, anterior, middle, and posterior consonants in babbling.

• A sharp predominance of labial and laryngeal sounds in babbling.

Techniques for stimulating babbling

• Moments of absolute silence are created when the child can listen to an invisible but close source of sounds (human speech, melodic chanting, playing a musical instrument). To induce speech imitation, you should be in the baby’s field of vision, teach the child to voluntarily pronounce first those sounds that are in his spontaneous babble, and gradually add new sounds and syllables that are similar in sound. It is useful to include the child in a group of babbling children (Borodich A.M., 1981).

• The baby extracts the material for babbling from the environment himself, which is why he needs sounding toys so much. In addition to them, children also benefit from those that “ring, knock, moo, whistle, hiss...” He will listen to their sounds and from each sound extract something of his own, which is reflected in babbling (Wiesel T.G., 2005).

• The unhindered development of the entire motor system has a huge impact on the development of the child’s language (Tikheeva E.I., 1981).

• Play with your baby while sitting face to face.

• Repeat after your child the sounds he makes. Pause to give him the opportunity to respond to you.

• Imitate baby babble. Try to fully maintain the pace, timbre and pitch of the child’s speech. When pronouncing labial sounds and syllables, draw the child's attention to your mouth. Pause, giving your child time to repeat the sounds.

• Use a combination of chains of movements with chains of syllables: when pronouncing syllables, for example, ba-ba-ba, ma-ma-ma, jump with the child. To do this, you can sit the child on a large ball, another springy surface, or simply on your lap.

• Playing with a pacifier can be recommended to stimulate the lips. The adult “takes” it from the child so that the baby follows with his lips.

• Place your index finger on the upper lip, make stroking movements towards it from the nose (Solomatina G.N., 2004).

• During this period, it is advisable to encourage the adult to pronounce simple syllables. It is recommended to chant simple syllables and words:

• Ma-ma-ma-ma, mommy! Pa-pa-pa-pa, daddy! Ba-ba-ba-ba, grandma! Moo-moo-moo, little murochka! Ki-ki-ki-ki, little kitty!

• Conduct passive articulatory gymnastics.

• Stimulate the ability to localize sound in space not only to sound stimuli, but also to the child’s name. Gradually introduce sounds that differ in pitch, strength, and duration.

• During activities with a child, they attract his attention not only to toys, but also to his surroundings. They strive for the child to recognize the mother, to become wary at the sight of the mother’s unexpectedly changed face, for example, putting on a mask or throwing a scarf over her face. During this period, specially selected toys, different in size, color, shape, moving, and sound, become important. They strive to attract attention to the toy, to manipulate it, they hide toys in order to evoke an emotional attitude towards each toy individually, to highlight the toy that is most interesting and loved by the child.

• Stroking the fingertips with a stiff brush continues for some time. Brushes should be bright and different in color.

Literature

Belyakova L.I., Dyakova E.A. Stuttering. Textbook for students of pedagogical institutes in the specialty “Speech Therapy” - M.: V. Sekachev, 1998. - 304 p.

Vinarskaya.E.N. Early speech development of a child and problems of defectology: Periods of early development. Emotional prerequisites for language acquisition. - M.: Education, 1987 Sapogova E.E. Psychology of human development. - M.: Aspect Press, 2001 - 460 p.

Wiesel T.G. Fundamentals of neuropsychology: textbook. for university students. - M.: ASTAstrel Transitbook, 2005. - 384 p.

Glukhov V.P. Fundamentals of psycholinguistics: textbook. manual for students of pedagogical universities. - M.: ACT: Astrel, 2005. - 351 p.

Mikirtumov B.E., Koshchavtsev A.G., Grechany S.V. Clinical psychiatry of early childhood. - St. Petersburg: Peter, 2001. 256 p.

Arkhipova E.F. Speech therapy work with young children: a textbook for pedagogical students. universities - M.: AST: Astrel, 2007. - 224 p.

Neiman L.V., Bogomilsky M.R. Anatomy, physiology and pathology of the organs of hearing and speech: Textbook. for students higher ped. textbook institutions / Ed. IN AND. Seliverstova. - M.: VLADOS, 2001. - 224 p.

Borodich A.M. Methods for developing children's speech. - M.: Prochveshchenie, 1981. - 256 p.

Isenina E.I. Parents about the mental development and behavior of deaf children in the first years of life. - M.: JSC IG "Progress", 1999. - 80 p.

Tikheyeva E.I. Speech development in children (early and preschool age). – M.: Education, 1981

Solomatina G.N. Stimulation of speech development in children with congenital cleft lip and palate.//Speech therapist. – No. 2. – 2004.

Sources: https://logomag.ru/blog/ontogenez/136/

https://logomag.ru/blog/ontogenez/137/

https://www.theplace.ru/photos/photo.php?id=308561

Speech development of children in ontogenesis

Yulia Sergeeva

Speech development of children in ontogenesis

Speech development of children in ontogenesis

Ontogenesis of speech development is the sequence of development of the aspects and components of speech in children at different stages of socialization.

In the literature, quite a lot of attention is paid to the issues of the gradual development of speech during its normal development . The works of A. N. Gvozdev, D. B. Elkonin, A. A. Leontyev, N. Kh. Shvachkin, V. I. Beltyukov describe in detail the formation of speech in children starting from infancy. Researchers identify a different number of stages in the development of children's , call them differently, and indicate different age boundaries.

N.V. Nishcheva [40] noted that the appearance and further development of speech depends on a number of factors:

a certain degree of maturity of the cerebral cortex;

a certain level of development of all senses ;

the presence of a speech environment , speech environment ;

state of the child’s psychophysical health;

the need to use speech as the main method of communication.

A. N. Gvozdev traces the sequence of appearance of various manifestations in a child’s speech and, on this basis, identifies a number of periods: the period of various parts of speech; period of phrases; period of different types of proposals. A. N. Gvozdev considers the formation of speech in a linear sequence: babble - words - phrases - sentences - coherent speech [13].

E. N. Vinarskaya divides of speech development

period of prephonetic universals;

the period of phonetic images and gestures;

period of phonetic representations;

period of phonemic generalizations.

N.S. Zhukova identified two periods of speech development : preverbal and verbal. N. S. Zhukova identified five stages development from birth to 18 months:

Stage 1 – from birth to 8 weeks (2 months), characterized by reflexive cries and sounds.

Stage 2 – characterized by qualitative changes in screaming, the appearance of humming and laughter.

Stage 3 – characterized by the appearance of babbling.

Stage 4 – the blossoming of babbling, or the stage of canonical vocalization. Period 5-7, 5-12.5 months. This stage is characterized by the repetition of two identical syllables (ba-ba, yes-da, ma-ma)

. At this stage, control over the pronunciation of sounds increases.

Stage 5 – covers the period from 9 to 18 months. At this stage, babbling words appear[59].

S. N. Tseitlin wrote: “About two months, the child begins to develop clearly articulated sounds and, most importantly, it becomes noticeable that he himself enjoys them. This is a hum, so called because of its resemblance to the sounds made by pigeons. By three months, buzzing usually reaches its maximum. The next stage of pre-speech vocalizations is babbling . If humming includes sounds reminiscent of vowels, then babbling is a combination of sounds that are more like combinations of a consonant + vowel” [60, p. 192].

Before the transition to words, proto-words appear that have the following characteristics:

simplicity of sound appearance;

accessibility for articulation at a young age;

motivation of a sound form that is understandable to

child "sound-imaginative"

character.

S. N. Tseitlin [60] identifies the following stages of speech ontogenesis : preverbal stage; stage of one-word statements; stage of initial two-component utterances; stage of elementary complex sentences; transitional stage to systemic speech.

L. studied the early . I. Belyakova, and based on the research, determined the following ontogenesis of speech :

At 16-20 months of life, most children vocabulary expands especially intensively. Many words are initially conveyed by a rhythmic structure or a stressed syllable.

At 18-22 months of life, the formation of elementary phrasal speech occurs. The first phrases consist of 2-3 words that have not yet been combined into syntagma, and the word is accompanied by a gesture.

At 28-32 months of life, phrasal speech begins to become increasingly complex and intensively used in the active speech of children . Grammatical forms become normative.

During early childhood, the active vocabulary increases sharply, as children vocabulary is updated, and words transition from the passive to the active vocabulary of children [31] .

O. E. Gromova examines the relationship between development and the psychological development of children and focuses on the following periodization: pre-speech stage ; stage of primary language acquisition; stage of mastering basic grammatical rules; stage of assimilation of morphological, phonetic norms and development of coherent speech .

O. E. Gromova notes that the early age period is key in mastering the native language and depends on the social environment, speech environment , and educational conditions.

Thus, speech formation occurs up to 3 years. This period is called the sensitive period of speech development , it is associated with the structure and development of the brain structures of a young child.

D. B. Elkonin established that during early childhood speech acts as a means of communication and has a practical orientation and situational nature.

D. B. Elkonin wrote: “Changes in a child’s lifestyle, the emergence of new relationships with adults and new types of activities lead to differentiation of functions and forms of speech” [62, P. 7].

The child moves to contextual speech and to a monologue form of communication. S. Ya. Rubinstein believed that contextual speech better reveals the thoughts of other people, regardless of the situation.

A. M. Leushina, studying the patterns of speech development in children , noticed that children’s can be situational or contextual, depending on the conditions of communication.

N.V. Nishcheva highlighted the characteristics of speech development , the parameters of which should be addressed by the speech therapist and parents[41].

From birth to 8 weeks. During this period, it is necessary to pay attention to reflexes - sucking, grasping. Negative signs can be noted: screaming and crying without an objective reason (when the cervical vessels are blocked, intracranial pressure rises, headache, and in a child this manifests itself in screaming); hypertonicity or hypotonicity, unilateral or bilateral; minor hyperkinesis; unusual posture of the child; paresis of the tongue.

After 2-5 months, humming appears, preparing the articulation of vowel sounds and speech breathing .

From 5 months to 12 months is a period of babbling according to 2 rules: syllables with labial sounds and imitative imitation. If the child does not start babbling, then there may be problems with hearing, and the child should be referred to an otolaryngologist.

By 10 months, the child adds gestures, reinforcing babbling speech.

By the age of one year, a child’s vocabulary consists of 10-15 conscious babbling words and onomatopoeia. At 1.5-2 years old, the child begins to make sentences using verbs. From the age of 2.5 years, the grammatical structure of speech begins to form; if this does not happen, then the child may have delayed speech development .

By the age of 3, the child constructs simple common sentences. There is a qualitative and quantitative leap in speech development , all parts of speech are formed. ontogenesis begin . At 5 years old, the child uses complex sentences, hissing and sonorant sounds appear. At 6 years old, children have correct articulation. From 7 to 17 years of age, a child masters written speech[33].

According to B. M. Grinshpun [18], the following patterns of speech development :

1. Period of development of pre-speech speech (1 year of life)

.

From 3-6 months the stage of humming, which reflects the physiological comfort of the child. Babbling appears from 6 months. Babbling does not appear in all children : it is absent in deaf children and alaliks. mentally retarded and otherwise Babbling is the repeated repetition of syllables whose combinations have no semantic meaning. , speech breathing is trained . articulatory apparatus. The nature of babbling can reflect problems in the development of the child (in children with damage to the central nervous system, monotonous quiet babbling, breathing quickly depletes, and a hoarse voice).

2. Period of speech development (1 -1.5)

.

The first words appear in the child’s dictionary. The number of words is from 8 to 12, most of them are babble and onomatopoeia; these words receive subject assignment. The following sounds receive subject correlation: labial-labial (b, p, anterior lingual stops (d, t, vowels). Speech understanding is limited, since the child knows the names of several toys and household items.

3. Period of speech development (1.5-2)

.

The child strives for verbal communication with an adult. The child himself expresses his desires and shows the formation of the intonation side of speech. By the end of 2 years, the child’s vocabulary is 200 words. During this period, a stable formation of a sequence of 2-3 syllables and sounds: labial-dental (v, f, soft (l, nasal sonorant (n), back lingual (k, g, x)

. A child can retain in memory and carry out 2-step instructions. Behavior is not regulated by the speech of an adult[27].

4. Period of speech development (2-3)

.

A child's vocabulary is 1000 words. The child is very active in speech. By the age of 3, the process of phonemic education ends. The child may not speak hissing, hard l and r - more often he replaces them with simpler sounds of articulation.

A rapidly increasing vocabulary does not allow the child to clarify the pronunciation of each word, and adults must listen carefully to the child’s speech, understand it and repeat correctly those words that he distorts. Hearing the correct pronunciation of words, the child will gradually correct his speech.

The younger the children, the less able they are to analyze their pronunciation. They are interested in the content of speech, they are attracted by its intonation, expressiveness, and they do not notice the shortcomings in the pronunciation of individual sounds. After 2-3 years, children are already able to notice incorrect pronunciation in their friends, and only after that they begin to pay attention to their own pronunciation and gradually improve it.

The child does not understand and does not independently construct sentences that reflect cause-and-effect relationships, since thinking is still visual and effective. There are many errors associated with the use of words excluded from the rules; neologisms appear. (in children with mental retardation, neologisms appear at 6-7 years of age, but in mental retardation they do not appear).

Egocentrism of speech leads to the development of inner speech , and then verbal-logical thinking. Speech is situational.

5. Period of speech development (3-5 years)

.

In the third year of life, the child begins to pay attention to how this or that sound is pronounced, looks at the lips of the speaker, looks into the mother’s mouth to see how she said it, and thus makes it easier for himself to pronounce a new sound or word. The spoken word is controlled by the ear, and thus, in the close interaction of articulation and auditory perception, correct pronunciation is formed. Not all children go through this process easily. There are often cases when a child cannot copy the correct movement, find the desired position of the tongue, and then a distorted, incorrect sound is obtained. An example of the distortion of whistling and hissing sounds is their lateral and nasal pronunciation.

The formation of the phonetic-phonemic side of speech ends. All sounds must be differentiated, and the lexical and grammatical structure of speech is improved. Well- developed monologue speech (retelling, story)

. Speech is contextual. A sense of language norm is formed. Prerequisites for mastering the reading process appear[10].

A.I. Ivanova considers two components of the development of speech functions in ontogenesis : the perception of someone else’s speech and the formation of one’s own speech.

The classical periodization of the development of children's speech , generally accepted in modern works, comes down to identifying three stages:

pre-speech , divided into the period of humming and babbling;

the stage of primary language acquisition, that is, pre-grammatical;

stage of grammar acquisition. Those grammatical forms appear that help the child navigate in relation to objects and space (cases, in time (verb tenses)

. The accusative case appears first, then the genitive, dative, instrumental and prepositional.

We can highlight the main patterns of normal speech development :

1. Impressive speech (understanding)

in relation to expressive speech.

2. Structural components of the language: vocabulary, grammar, phonetics develop unevenly (vocabulary and grammar advance, phonetics lags behind)

.

3. The semantic side of a child’s speech is ahead of the development of the formal side of speech.

Thus, the development of speech in preschool age follows two lines: the impressive side of speech is improved and the child’s own active speech is formed.

Genesis of vocalizations in the preverbal period

Mishina G.A., Chernichkina Yu.D. Bulletin of the Orthodox St. Tikhon's Humanitarian University. Series 4: Pedagogy. Psychology Issue No. 23 / 2011

Many researchers from various fields of science have studied the concept of vocalization. Hence, there is no unambiguous definition of the concept of “vocalization”. Some researchers call vocalizations all the child’s vocal reactions that are not endowed with a specific meaning (words) (I.N. Gorelov, E.I. Isenina, etc.). Other researchers classify as vocalizations only the communicative sounds of a child that are not related to verbal speech (G.V. Kolshansky, S.L. Rubinstein). The authors also disagree regarding the nature of vocalizations. When considering the concept of vocalization, some authors are adherents of the biological theory of speech ontogenesis, suggesting that the language ability is innate (T.V. Bazzhina, A.N. Gvozdev, N. Chomsky, S.N. Tseitlin, etc.). This opinion is supported by empirical data that cry is present in all infants, even deaf ones (T.V. Bazzhina, V.I. Garbaruk, I.V. Dmitrieva, I.E. Isenina, etc.). The absence of pauses in the cry indicates that the child does not expect an answer, which also confirms the non-communicative nature of the cry at the initial stage (J. Bruner). It is difficult to identify the structure of such a signal (T.V. Bazzhina, E.N. Vinarskaya, S.V. Grechany, A.G. Koshchavtsev, J. Linda, B.E. Mikirtumov, H. Trali, etc.); and this is its similarity with animal signals, which are also structureless (N.I. Zhinkin). The first month of life for all children is characterized by the predominance of crying with passive detached intonations and, in general, there is no big difference in crying between groups of children raised in different social conditions (in the family and in the orphanage) (N.Ya. Kushnir, Solomatina T.V. ). Other authors lean more toward social theory, believing that the ontogenesis of speech is the result of mental development and social influence (S. Büller, J. Piaget, etc.). Examples of Mowgli children are given as evidence.

In our study, we proceeded from the position of L.S. Vygotsky about the unity of biological and social factors in the mental development of a child: the prerequisites for speech are biologically determined, but at the same time, the social factor of the child’s development plays a great role. In our opinion, when a child’s cry, as an unconditionally reflexive act in the process of development of brain structures and under the influence of the social environment, becomes a conditioned reflex and acquires intonation shades of resentment or dissatisfaction, we can already talk about the manifestation of the directionality of vocalizations. Up to 6 months, according to research by physiologists, vocalizations are completely biologically determined and are unconditional and conditioned reflex reactions in the structure of the first signal system (L.O. Badalyan, M.M. Koltsova). In the first months of life, all sensations that the child receives from the external environment are merged. According to physiologists (L.O. Badalyan, M.M. Koltsova), the more often the same stimuli are re-excited, the faster the child’s reflex-type response is formed and improved, and, consequently, the child’s sensations will become more differentiated . Thus, in the process of regular contact with an adult, the infant develops a conditioned reaction of a social nature. From 2 months of age, a child is characterized by various ways of displaying emotions: peace, satisfied humming, dissatisfied whimpering, crying, intonation of joy in the structure of the revitalization complex, intonation of reproach, demand and surprise. By 6 months, due to the development of the acoustic zones of the brain and as the main process of myelination is completed, the child already becomes able to perceive and differentiate individual words, the second signal system begins to develop (L.O. Badalyan, M.M. Koltsova, I.P. Pavlov ). At the same time, the role of an adult in the child’s speech development remains leading and decisive: if in the first half of the year the child did not receive proper social contact and communication with an adult, then the development of the second signaling system may be delayed or disrupted.

The existing periodizations of speech development of a child in the first year of life were developed depending on the approach in the light of which vocalizations were considered - psychological, linguistic and psycholinguistic, phonetic, semiotic (T.V. Bazzhina, E.N. Vinarskaya, L.S. Vygotsky, A. N. Gvozdev, I. N. Gorelov, N. I. Zhinkin, E. I. Isenina, G. V. Kolshansky, A. R. Luria, S. L. Rubinstein, M. E. K. Halliday, S. N. Tseitlin, F.Ya. Yudovich, etc.).

Traditionally, linguistic periodization of speech is used, highlighting the following stages of the pre-speech period of development: screaming, humming and hooting, babbling. Most researchers from different fields of science use this periodization. The phonetic approach (T.V. Bazzhina, V.I. Beltyukov, A.N. Gvozdev, etc.) allows us to consider vocalizations mainly from the acoustic side. Psycholinguistics considers speech utterances from the point of view of the patterns of their generation and perception (N.I. Gorelov and others). Psychology studies speech from its “internal” side. Speech is considered both from the point of view of reflexes and from the point of view of its internal organization, with particular importance in determining vocalizations given to communication. The semiotic approach allows us to consider vo-signs as part of a broader sign structure - a combination of signs of a proto-language - and thereby include gestures, actions and situation objects in the linguistic structure.

However, even within the framework of one approach to the study of vocalizations, different researchers can characterize each period of speech ontogenesis differently. For example, according to T.V. The bazzhin cry cannot be interpreted as one of the stages of preparation for speech, since the cry develops in the direction of increasing the total sound time of the cry period, and from the point of view of the principle of saving effort, speech sounds should develop in the direction of reducing the sound time. In addition, the vocal cords do not take part in the production of a cry; the production of a cry is associated with the work of the respiratory apparatus (E.N. Vinarskaya). T.N. Ushakova believes that the function of a cry contains the germ of a future verbal sign. According to the author, from the first days a child is able to convey his internal psychological state through screaming.

When studying babbling, some authors (E.I. Isenina) believe that babbling is an expression of not only emotional expression and attitude towards the speaker, but also conveys the child’s attitude towards surrounding objects and characterizes the communicative type of utterance. And others (A.N. Gvozdev, S.N. Tseitlin) believe that babbling is not a sign, i.e. does not convey information, does not reflect thought and therefore cannot be regarded as a means of communication.

I would like to separately highlight the periodization of speech development proposed by E.N. Vinarskaya, since the author considers the process of speech ontogenesis from the position of the unity of biological and social factors. The researcher distinguishes 2 periods of pre-speech development of the child: the period of pre-phonetic universals and the period of phonetic images and gestures (paralinguistic means of emotional expressiveness). According to the author, at the beginning of the period of pre-phonetic universals, self-regulation of the newborn’s body is carried out on the basis of a defensive reflex, which is expressed in the form of an emotionally negative reaction of the child - a cry. Further, throughout infancy, under the influence of a close adult, the child’s communicative and cognitive development occurs, the basis of which, instead of a defensive reflex, becomes an indicative and exploratory one. The author considers humming and babbling, as emotionally positive reactions, to be signs of paralinguistic means of emotional expressiveness that serve the purposes of communication and cognition, and not defense, like screaming. Thus, as the child develops, vocalizations, being initially biological, unconditionally reflex reactions, gradually, under the influence of contact with an adult, turn into socially conditioned conditioned reflex reactions, and become means of communication of the child with the outside world.

It is important to take into account the social factor when considering dysontogenesis of speech. In the course of analyzing the process of speech development and its dysontogenesis, not all authors take into account, along with the physiological (sensorimotor) factor of the problem, the social factor, as one of the leading factors in the structure of the disorder. When identifying dysontogenesis of speech development and determining its causes, it is very important to take into account the state of all prerequisites for speech development, and not just cognitive and neurophysiological ones.

Over the past few years, we have conducted an experiment that was aimed at studying the ontogenesis of speech in the preverbal period. The vocal production of infants in the normal group and in cases of complicated development was studied. 16 children aged from 2–4 months to 3 years took part in the longitudinal study. During the first 3 years of the child’s life, once every three months, an hour-long filming of each subject was carried out during his natural behavior at home. The state of vocal manifestations and their direction were recorded. As a result of the analysis of the obtained material, a number of conclusions were made. It was noted that, starting from the 2nd month of life, children’s vocalizations manifest themselves in both communicative and non-communicative situations: non-communicative vocalizations accompanied the child’s actions, were an indicator of the child’s emotionally positive state, and were not aimed at communication; communicative vocalizations had various purposes, realized in the process of communication with surrounding adults.

Depending on the approach to considering vocalizations, researchers identify various functions. A number of researchers distinguish two functions in a cry: service-physiological and conditionally commutative (informative) functions (T.V. Bazzhina), while the cry acquires communicative meaning only for an adult; With the development of the child’s body and his psyche, the cry acquires an expressive function, gradually transforming into crying. And crying is already a communicative means; a means of influence, and a targeted one, on an adult, i.e. is communication with goal setting.

Other authors (E.I. Isenina) do not assign screaming any functions at all, saying that screaming only accompanies the child’s desires, but does not express them. In foreign literature, the most developed classification is M.E. K. Halliday, including such functions of vocalizations as: instrumental, informative, regulatory, interaction, personal, heuristic, imagination. On this basis, a periodization of the development of vocalization functions in the preverbal period was created (E.I. Isenina).

Within the framework of the model of the speech-language mechanism, such functions as the function of symbolization, representation, expression are identified, while the expressive function is considered as the main one and manifests itself in the form of intentions - intentions to highlight hidden mental contents in the external plane (T.N. Ushakova, S.S. Belova ). The following groups of intentions and the time of their appearance were identified:

1) object intentions (desire to receive or reach an object - 5–6 months, desire to perform an action with an object - 10 months, urging an adult to do something with an object - 14 months, expressions of regret in an unsuccessful attempt to get an object - approximately 10–11 months, expression of pleasure when receiving an object - from about 10–11 months);

2) social and communicative intentions (the desire to be held by an adult - 1–7 months, pleasure from communication, requests, drawing attention to oneself, anxiety about the absence of an adult, etc.); - intentions of protest or refusal (stopping the actions of others, demonstrating a negative attitude towards what is happening - 13 months); - intentions to attract an adult to joint activities (in situations of play, reading and other activities);

3) commenting intentions (in the situation of playing, walking, repeating words after an adult, reading, etc.) - 11 months. However, according to the results of data processing, only two intentions received reliable temporal localization: “the desire to receive an object” and “the desire to return an absent adult” (S.S. Belova).

A study conducted by E.I. Isenina, showed slightly different time periods for the manifestation of similar linguistic functions of vocalizations: - interaction, personal, instrumental (2 - 6-7 months); — informative, regulatory, imagination (8–9–12 months); — heuristic (12–24 months).

As noted by N.I. Zhinkin, speech is not only a manifestation of language, speech has its own structural and functional features. The classification of speech functions is widely represented in psychology (L.S. Vygotsky, A.R. Luria, S.L. Rubinstein, F.Ya. Yudovich). S.L. Rubinstein wrote that speech exists only where there is semantics, meaning that has a material carrier in the form of sound, gesture, visual image. Meaning is a function of speech as an activity. Consequently, speech is speech when it has a function. L.S. Vygotsky identified the following functions of speech: nominative, indicative, regulatory and significative functions.

S.L. Rubinstein believed that speech has one main function - communication. The function of communication or message - the communicative function of speech - includes the following functions: emotional, expressive (expressive) and impactful (motivational). Speech in the true sense of the word is a means of conscious influence and communication carried out on the basis of the semantic content of speech.

The functions of vocalizations, as well as the vocalizations themselves, appear and develop gradually in the process of general ontogenesis, i.e. go through their own development path. And the process of communication between a child and others directly influences the development of vocalization functions. If the social development of a child is distorted, disrupted, or delayed for any reason, then this has a direct impact on the genesis of the functions of vocalizations.

Determining the level of development of vocalization functions during the diagnostic process allows us to give an objective and more complete assessment of the preverbal and verbal period of speech development of a child of infancy and early age. Our research has shown that in the process of diagnosis and correctional work with a child, it is important to take into account not only the physiological, sensorimotor, cognitive factors of the child’s development in general and his speech in particular, but also the social factor; It is necessary to take into account not only the physiological stages of development of linguistic means in the 1st year of a child’s life, but also the nature of the semantic content of these means.

Bibliography

1. Badalyan L.O. Child neurology. – M., 2001. 2. Bazzhina T.V. Psycholinguistic analysis of some stages of pre-speech development/ Formation of speech and language acquisition by a child. - M., 1985, p. 6–20. 3. Beltyukov V.I., Salakhova A.D. Babbling of a hearing child // Questions of psychology, No. 2, 1973. 4. Vinarskaya E.N., Bogomazov G.M. Age phonetics. - M, 1987. 5. Vinarskaya E.N. Early speech development of a child and problems of defectology. – M., 1987. 6. Vygotsky L.S. Psychology of child development. – M., 2004. 7. Gvozdev A.N. Issues in studying children's speech. - M., 1961. 8. Gorelov I.N., Sedov K.F. Fundamentals of psycholinguistics. - M., 1997. 9. Zhinkin N.I. Mechanisms of speech. - M., 1958. 10. Isenina E.I. Psycholinguistic patterns of speech ontogenesis (Preverbal period). - Ivanovo, 1983. 11. Isenina E.I. Preverbal period of speech development in children. - Saratov, 1986. 12. Kolshansky G.V. Paralinguistics. - M., 1974. 13. Koltsova M.M. The child learns to speak. - M., 1973. 14. Luria A.R., Yudovich F.Ya. Speech and the development of mental processes in a child. - M., 1956. 15. Mikirtumov B.E., Koshchavtsev A.G., Grechany S.V. Clinical psychiatry of early childhood. - St. Petersburg, 2001. 16. Piaget J. Speech and thinking of a child. - Moscow, 2008. 17. Child’s speech: problems and solutions. Ed. Ushakova T.N. - M., 2008. 18. Rubinstein S.L. Fundamentals of general psychology. – St. Petersburg, 1999. 19. Khomskaya E.D. Neuropsychology: 4th edition. - St. Petersburg, 2005. 20. Tseytlin S.N. Language and the child. Linguistics of oral speech. - M., 2000.

![Hard and soft sound [d]](https://ls-kstovo.ru/wp-content/uploads/tverdyj-i-myagkij-zvuk-d3-330x140.jpg)