Psychology of communication on Igor Garshin’s website.

Oratory Home

| Write |

Home > Esoterics > Psychology > Psychology of communication

Alphabetical list of pages: | | | | | E (Yo) | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 0-9 | AZ (English)

| All great events begin with communication. Speak so I can see you. (Socrates) The most important thing in communication is to hear what was not said (Drucker) |

At first, this section on communication skills was combined with public speaking into the subsection “Psychological Influencing Skills.” Oratory art has remained there, because, if you look at the root, the goal of the speaker is to convince listeners that he is right, to influence him (the same applies to discussions). And communication is the pleasure of mutual understanding. If one of the interlocutors feels that they are “treating their brains,” communication will stop. Although, on the other hand, if communication is pleasure, then what is there to learn? They learn to solve problems, that is, again, to convey a thought, to influence.

Sections of the page about psychology and communication skills :

- Oratory (rhetoric, ability to persuade)

- Demanipulation (the ability to resist false beliefs)

- Conflictology (countering hostility)

- Understanding social cues

- Transactional psychology

- Influence by behavior [education by example]

- Hypnosis, self-hypnosis (auto-training) and getting rid of hypnosis

Read about the psychology of love and family relationships on the Yin and Yang page.

Oratory (rhetoric, ability to persuade)

The word is man's most powerful weapon. (Aristotle)

What is good and bad in a person at once - Language. (Anacharsis)

The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle said that Empedocles invented rhetoric.

Oratory is not just communication. Firstly, this is the impact

in a word (as in education) - through impression, logic and even pseudo-logic. Secondly, the impact is not on one or two, but, as a rule, on a large group of people who, often, are unfamiliar to you. On the other hand (plus), your monologues here can be longer than when communicating with one or several people - and you can have time to get your point across, since the conversation with the team follows certain rules (otherwise it is unconstructive for both sides).

Rhetoric is the study of oratory, the theory of eloquence. Logic and rhetoric are interconnected. But the art of persuasion is not only the power of logical arguments. Logical argumentation, all the power and strength of evidence cannot convince a person who does not want to change his position. Therefore, rhetoric is not limited to the area of reliable knowledge [!]. Since the practice of human communication is not reduced to chains of strict logical reasoning, but, on the contrary, very often encounters unexpected actions and original statements, it is precisely these statements (metaphors, catchphrases) that give many speeches a special persuasiveness that has the greatest impact on listeners [through the subconscious ]. Conviction consists not only of understanding, but also of faith. And speech is built not only from words, but also from gestures. Oratory should not only convince, but excite and delight.

Examples of eloquence are, for example, the speeches of religious thinkers. Their features:

- great inner conviction of the truth of what is preached;

- absolute knowledge of the subject;

- accessibility of the material, richness in tropes and figures of rhetoric;

- the high goal of each sermon, its focus on good;

- thoroughness of preparation ( hermeneutics

) and constant internal readiness for performance.

- Courses in public speaking and communication skills.

Aspects and rules of rhetoric

To ask the right question, you need to know most of the answer. (R. Sheckley)

There are various aspects to the art of argument and persuasion.

- Three types of eloquence

: 1) solemn (praising and blaming speeches); 2) deliberative or political (speeches persuasive and dissuading); 3) judicial (speeches accusing and defending). - Three types style

: 1) the middle style, designed to please the listener, appropriate in the solemn (epidictic) type of eloquence; 2) an elevated style, aimed at touching the listener, which was intended for deliberative eloquence; 3) a dry style, convenient for teaching, best suited for judicial eloquence. - Rhetorical speech

and its rules: 1) choosing a topic or finding; 2) location of the material; 3) presentation or verbal expression; 4) memorization and its techniques; 5) pronunciation. - Invention

(in Aristotle - “proof”) is

the doctrine of morals

, arguments and passions with the aim of finding means of persuasion. Morals are moral qualities that allow the rhetorician to establish his authority. The rules of morals are as follows: 1) demonstrate seriousness, modesty, caution; 2) avoid anything that may create the impression of a lie; 3) use “mores” in the introduction; 4) affectation should be absent. General rules of invention: 1) morals, arguments, passions must cooperate in the name of a single goal - conviction; 2) one of the three parts must dominate; 3) morals and passions are addressed to the weak, sensual and youth; 4) arguments in speech - to sedate and reasonable people; 5) abuse of morals and passions is easily ridiculed; 6) reflection, experience and careful study of the heritage of great teachers are necessary for the formation of taste, which dictates the right choice and measure. - An argument

is a form of reasoning that derives something new from known propositions. The actual arguments are a syllogism (very rarely), an enthymeme, an epicheireme, a dilemma, a sorites, an example (one of the premises of which is a historical fact, a striking event), induction, a “personal” argument, i.e. a conclusion arising from the words or actions of an opponent. The main task of a rhetorician is to present convincing arguments. The difference between rhetorical argumentation and logical argumentation: various verbal decorations; the consequence must precede the premise. Rules of arguments: 1) evidence is the basis of oratory; 2) evidence should not be multiplied so much as weighed; 3) it is necessary to discard arguments that can be refuted. - The doctrine of passions

(

pathetics

) as the idea of two main passions - Love and Hate, which form all other secondary feelings. The success of Demosthenes is not a refined technique, but a developed pathos, embodied in passionate patriotism. Rules of passions: 1) call on the help of passions only to potentially pathetic objects; 2) save the sensory effect for the end of the performance; 3) avoid excessive pathos that causes ridicule. So, the triune goal of a rhetorician is 1) to attract with character, 2) to convince with argument, 3) to touch with feeling. - Disposition

is the arrangement of the elements obtained as a result of the invention to best persuade the audience (Pellissier).

The disposition contains an introduction to the topic (“engaging the plot”) and development (“bringing evidence”). The speech being composed has six parts: 1) introduction, 2) sentence (theorem); 3) narration; 4) confirmation; 5) refutation; 6) conclusion. Three types of introduction: direct, indirect and sharply emotional. Rules for introduction: 1) overall success depends on introduction; 2) “mores” should be used; 3) write an introduction based on the essence of the topic under consideration; 4) write the introduction last; 5) accessibility of style; 6) avoid the banal and extravagant. A sentence ( theorem

) is an optional element, usually included when the nature of the topic is complex and unobvious. - Narration

(

narration

) is a presentation of the factual aspect of the topic. Rules of narration: 1) the narration should touch only on basic facts that are directly related to the topic; 2) the facts must be plausible; 3) the narration should be short and clear; 4) interest in speech depends on the interest caused by narration; 5) narration must be accompanied by a description to revive dry facts; 6) choose the most advantageous point of view for description; 7) when describing, avoid vagueness and unnecessary details; the place of description is at the beginning of the narration.

Rules of narration: 1) the narration should touch only on basic facts that are directly related to the topic; 2) the facts must be plausible; 3) the narration should be short and clear; 4) interest in speech depends on the interest caused by narration; 5) narration must be accompanied by a description to revive dry facts; 6) choose the most advantageous point of view for description; 7) when describing, avoid vagueness and unnecessary details; the place of description is at the beginning of the narration. - Confirmation

(

confirmation

) is the main deployment of argumentation with the aim of proving the truth of the premises put forward in a sentence. Confirmation rules: 1) all comments regarding the application of the necessary evidence must be collected together; 2) for this purpose, carry out an audit of all commonplaces considered in the Convention; 3) when choosing arguments, care about their quality, not quantity; 4) the best is the Homeric order: first there are strong arguments, then a lot of average ones, at the end there is one most powerful argument; 5) carefully avoid descending order of arguments; 6) strong arguments - in a simple form; weak ones - group several for self-support. - Conclusion. Rules of the Conclusion: 1) a summary of the argument, developed in support and should evoke emotions; 2) accuracy of presentation and variety in style; 3) select the strongest points from the confirmation; 4) when using “passions”, remember moderation; 5) the style is lively and emotionally pompous.

- Elocution

(

eloquence

) is the verbal formulation of a thought. Its content: analysis of various grammatical forms (sentence, phrase, period); judgment about the main characteristics of the style and its varieties; the doctrine of the “forms” of style and the “forms” of speech (prose and poetry); description and classification of rhetorical figures. Elocution is a characteristic of the tropes and figures of the theory of eloquence. - Tropes

are phrases based on the use of words in a figurative meaning to enhance it. Paths of words: metaphor, metonymy, synecdoche, antonomasia, onomatopoeia, catachresis, metalepsis, etc. Paths of sentences: allegory, epitheton, emphasis, periphrasis, irony, hyperbole, euphemism, litotes, etc. - The figures

are sophisticated combinations of words. Figures of words and figures of thought. Figures of words: 1) figures of addition; 2) decreasing figures; 3) figures of location or movement. Addition figures: anaphora, epiphora, simploca, anadiplosis, gradation, polysyndeton. Decrease figures: ellipsis, syllepsis, asyndeton. Arrangement figures: inversion (anastrophe, hyperbaton), parallelism (isocolon, antithesis, homeotelevton), chiasmus. Figures of thought: definition, saying, rhetorical question, paralepsis, prosopopeia, appeal, liberty, doubt, supplication, exclamation, etc.

The meaning of metaphor in a rhetorician's speech

The best speaker is the one who, through his words, both instructs his listeners, and gives pleasure, and makes a strong impression on them. The greatest achievement of a speaker is not only to say what is needed, but also not to say what is not needed. (Cicero)

True eloquence is the ability to say everything you need to say, but nothing more.

(François de La Rochefoucauld

- like

Cicero

) Today we need to say only what is relevant today.

Put everything else aside and say it at the appropriate time. (Horace)

A beautiful thought loses its value if it is poorly expressed.

(Voltaire)

Speaking without thinking is like shooting without aiming.

(Miguel de Cervantes

, and also

Thomas Fuller

) He who cannot speak will not make a career.

(Napoleon Bonaparte)

There are three categories of speakers: some you can listen to, others you can’t listen to, and others you can’t help but listen to.

(Archbishop Magee)

A speech should have a good beginning and an effective ending.

But the main thing is that these two parts are closer to each other (Anthony Eden)

Logic is, apparently, the ability to prove some truth, and eloquence is a gift that allows us to master the mind and heart of our interlocutor, the ability to explain or inspire everything in him, whatever we want.

Jean La Bruyère

Metaphor is used in various fields of knowledge: from poetics and rhetoric to physics and mathematics. » The mystery of metaphor was studied by Aristotle and G. W. F. Hegel

,

F. Nietzsche, E. Cassirer, H. Ortega y Gasset

and many others.

There are two ways of looking at metaphor. Rationalists are opponents of the use of metaphor. They consider it unacceptable in scientific writings. But F. Nietzsche

writes about the fundamentally irreducible metaphorical nature of cognition.

E. Cassirer

believes that the metaphorical “mastery of the world” is the opposite of discursive thinking.

H. Ortega y Gasset

speaks of metaphor as a tool of thought that allows one to reach the most remote areas of the conceptual field.

Ortega

: “Metaphor lengthens the “arm” of the intellect; its role in logic can be likened to a fishing rod or a rifle.”

Interestingly, a change in the scientific paradigm is often accompanied by a change in the key metaphor, introducing a new area of similes and a new analogy.

Opinion of N.D. Arutyunova

: the study of metaphor is a rapidly expanding process, capturing all new areas of knowledge - philosophy, logic, psychology, hermeneutics, psychoanalysis, literary criticism, semiotics, rhetoric, theory of fine arts, linguistic philosophy, various schools of linguistics, cognitive sciences, artificial intelligence modeling.

Metaphor can be the key to understanding the foundations of thinking and the processes of creating not only a nationally specific vision of the world, but also its universal image.

Books about metaphor

Literature about the ability to make an impression with words:

- Arutyunova N.D.

Metaphor and discourse // Theory of metaphor. M., 1990. - Baranov G.S.

Scientific metaphor: Model-semiotic approach. In 2 parts. Kemerovo. Part 1. 1992; Part 2. 1993. - Borges H.L.

Metaphors of “1001 Nights” // Borges H.L. Letters of God. M., 1992. - Berkenlit M.B., Chernavsky A.V.

Construction of movement and metaphor of intelligence // Computers and cognition: Essays on cogitology. M., 1990. - Bessonova O.M.

Metaphor in a scientific context // Problems of interpretation in the history of science and philosophy. Novosibirsk, 1985. - Gusev S.S.

Science and metaphor. L., 1984. - Kassirer E.

The power of metaphor // Theory of metaphor. M., 1990. - Kuliev G.-G.

Metaphor and scientific knowledge. Baku, 1987. - Ortega y Gasset H.

Two great metaphors // Theory of metaphor. M., 1990. - Ortega y Gasset H.

“Taboo” and metaphor // Self-awareness of European culture of the 20th century: Western thinkers and writers on the place of culture in modern society. M., 1991. - Panov M.I.

This elusive metaphor (Review) // Philosophical Sciences: Abstract Journal. M., 1991. N5. - Petrov V.V.

Metaphor: From semantic representations to cognitive analysis // Questions of linguistics. M., 1990. N3. - Petrov V.V.

Scientific metaphors: Nature and mechanism of functioning // Philosophical foundations of scientific theory. Novosibirsk, 1985. - Tagliagambe S.

Visual perception as a metaphor // Questions of Philosophy. M., 1985. N 10. - Telia V.N.

Metaphorization and its role in creating a linguistic picture of the world // The role of the human factor in language. M., 1989.

New rhetoric (neorhetoric)

Neorhetoric, or new rhetoric (the name was introduced by University of Brussels professor Chaim Perelman) is being developed today at the intersection of linguistics, literary theory, logic, and philosophy.

There is a certain national “color” of the new rhetoric. In France, developments in the field of new rhetoric are associated with the activities of Roland Barthes; Metarhetoric, which deals with the theory of rhetoric and the interpretation of its concepts, has received the greatest development (in France, classic works on rhetoric by French authors of the 16th-18th centuries were republished, and modern researchers rely on them). In the USA, this is rhetorical criticism and rhetorical methodology. In Italy, neo-rhetoric develops within the framework of literary criticism. Two directions of new rhetoric in Belgium: 1) argumentative rhetoric (Perelman); 2) general rhetoric (“the mu group” from the University of Liege - Jacques Dubois and others - named after the first letter of the Greek word “metaphor”, the most remarkable, they believe, of the figures of rhetoric). The works of the “mu” group: “General Rhetoric” and “Rhetoric of Poetry”, which define rhetoric as a discipline that studies the techniques of speech activity that characterize, among other discourses, literary discourse. Discourse

- this is a coherent text in combination with pragmatic, sociocultural, psychological factors, or speech as a purposeful social component of the interaction of people and the mechanisms of their consciousness.

The emergence of new rhetoric gave the term “rhetoric” itself two meanings: 1) narrow - as a designation for a complex discipline that studies public speaking, 2) broad - in which the object of rhetoric becomes any type of speech communication, viewed through the “prism” of implementing a pre-selected influence on the recipient messages. In this case, rhetoric is the science of persuasive communication. Currently, a third point of view has emerged. It belongs to the modern Italian specialist in the field of semantics Umberto Eco, author of the novel “The Name of the Rose”. He believes that rhetoric is the science of generating statements. There is a new classification of figures of rhetoric by Roman Jakobson.

But most importantly, the development of cultural theory in the leading countries of Western Europe has caused close attention to the ideas and methods that were once developed by rhetoric a long time ago.

Books about neo-rhetoric

- Meizerovsky V.M.

Philosophy and neo-rhetoric. Kyiv, 1991. - Neorhetoric: Genesis, problems, prospects. M., 1987.

Carnegie's Outstanding Contributions

- .

Literature on the art of eloquence

I think I won’t be mistaken if I remain silent. (Murphy's Laws)

Classic works on public speaking

If you can't control your mouth, then don't even hope to control your mind. (Buddhist wisdom)

- Aristotle.

On interpretation // Aristotle. Op. In 4 vols. M., 1978. T.2. - Aristotle.

On sophistical refutations // Ibid. - Aristotle.

Poetics // Aristotle. Op. In 4 vols. M., 1984. T.4. - Aristotle.

Poetics // Aristotle and ancient literature. M., 1978. - Aristotle.

Rhetoric // Ancient rhetoric. M., 1978. - Aristotle.

Rhetoric. Book 3 // Aristotle and ancient literature. M., 1978. - Aristotle.

Topeka // Aristotle. Op. In 4 vols. M., 1978. T.2. - Arnaud A., Lanslot K.

General and rational grammar... (Grammar of Port Royal). M., 1990. - Arnaud A., Nicole P.

Logic, or the Art of Thinking, which, in addition to the usual rules, contains some new considerations useful for the development of the ability to judge. M., 1991. - Hermogenes.

About ideas, or about types of syllable // Living heritage of antiquity: Questions of classical philology. M., 1987. Issue. IX. - Demetrius.

About style // Ancient rhetoric. M., 1978. - Dionysius of Helicarnassus.

About connecting words // Ibid. - Dionysius of Helicarnassus.

Letter to Pompey // Ibid. - Zelenetsky K.P.

Theory of literature: Gymnasium course. In 4 vols. St. Petersburg, 1850-1860 (5 editions). T.1: Rhetoric. - Quintilian.

Twelve books of rhetorical instructions. In 2 parts. St. Petersburg, 1834. - Koshansky N.F.

General rhetoric. St. Petersburg, 1829-1949 (10 editions). - Lomonosov M.V.

A short guide to rhetoric for the benefit of lovers of sweet speech //

Lomonosov M.V.

Full collection op. M.; L., 1952. T.7. - Lomonosov M.V.

A short guide to eloquence. Book one, which contains rhetoric, showing the general rules of both eloquence, that is, oratorio and poetry, composed for the benefit of those who love verbal sciences // Ibid. - Merzlyakov A.F.

Brief rhetoric, or Rules relating to all types of prose writings. M., 1809-1828. (4 editions). - Nikolsky A.S.

Logic and rhetoric, presented in a concise way for children. St. Petersburg, 1790. - Plato.

Hippias the Greater // Plato. Op. In 3 vols. M., 1968. T.1. - Plato.

Hippias the Lesser // Plato. Dialogues. M., 1986. - Plato.

Gorgias // Plato. Op. In 3 vols. M., 2968. T.1. - Plato.

Euthydemus // Dialogues. M., 1986. - Plato.

Protagoras // Plato. Op. In 3 vols. M., 1970. T.2. - Plato.

Sophist // Plato. Op. In 3 vols. M., 1970. T.2. - Speransky M.M.

Rules of higher eloquence. St. Petersburg, 1844. - Cicero.

Brutus, or On Famous Orators // Cicero. Three treatises on oratory. M., 1972. - Cicero.

About the speaker // Ibid. - Cicero.

About the speaker // Cicero. Aesthetics: Treatises. Speeches. Letters. M., 1994. - Cicero.

About the State // Cicero. Dialogues. M., 1966; 2nd ed. 1994. - Cicero.

On the best form of an orator // Cicero. Aesthetics: Treatises. Speeches. Letters. M., 1994. - Cicero.

About finding the material // Ibid. - Cicero.

On the nature of the gods // Cicero. Philosophical treatises. M., 1985. - Cicero.

On the nature of the gods // Cicero. Aesthetics: Treatises. Speeches. Letters. M., 1994. - Cicero.

Orator // Cicero. Three treatises on oratory. M., 1972. - Cicero.

Topeka // Cicero. Aesthetics: Treatises. Speeches. Letters. M., 1994. - Cicero.

Tusculan conversations // Cicero. Favorite op. M., 1975. - Cicero.

Tusculan conversations // Cicero. Aesthetics: Treatises. Speeches. Letters. M., 1994.

Books on general rhetoric

Speak in such a way that you cannot be misunderstood. (Quintilian)

A great mind will show its strength not only in the ability to think, but also in the ability to speak.

(Ralph Emerson)

- Avelichev A.K.

Return of rhetoric // General rhetoric. M., 1986. - Apresyan G.Z.

Oratory. M., 1978. - Bezmenova N.A.

Essays on the theory and history of rhetoric. M., 1991. - Bezmenova N.A.

Theory and practice of the rhetoric of mass communication. M., 1989. - Gadamer G.-G.

Rhetoric and hermeneutics // Relevance of the beautiful. M., 1991. - Gindin S.I.

Rhetoric and problems of text structure // General rhetoric. M., 1986. - Gurevich S.S., Pogorelko V.F., German M.A.

Basics of rhetoric. Kyiv, 1988. - Oratory: Reader. M., 1978.

- Panov M.I.

Rhetoric from antiquity to the present day (Introductory article) // Anthology of Russian rhetoric. M., 1995. - Panov M.I.

Why is the art of eloquence needed today?

? // Buzuk G.L., Ivin A.A., Panov M.I.

The science of persuasion: Logic and rhetoric in questions and answers. M., 1992. - Soper P.L.

Fundamentals of the art of speech. M., 1992.

Popular scientific literature about the ability to think and persuade

Success

- this is a product of interesting thoughts and the ability to convey them.

Speak not in a way that is convenient for you to speak, but in a way that is convenient for the listener to perceive [NLP]. A good speaker is one who knows how to speak simply about complex things. Simplicity doesn't come easy. (Skilef)

The ability to convey a thought is simple:

- Baranov A.N., Kazakevich E.G.

Parliamentary debates: Traditions and innovations. M., 1991. - Voiskunsky A.E.

I say, we speak...: Essays on human communication. M., 1990. - Golub I.B., Rosenthal D.E.

Interesting style. M., 1988. - Grimal P.

Cicero. M., 1991. - Ivin A.A.

The art of thinking correctly. M., 1990. - Carnegie D.

How to develop self-confidence and influence people when speaking publicly // Carnegie D. How to win friends and influence people. M., 1989 (Numerous reprints). - Kokhtev N.N., Rosenthal D.E.

The art of public speaking. M., 1988. - Markicheva T.V., Nozhin E.A.

Public speaking skills. M., 1989. - Masters of eloquence. M., 1991.

- Micic P.

How to conduct business conversations. M., 1987. - Nozhin E.A.

Oral presentation skills. M., 1989. - Norman B.Y.

Language: Familiar stranger. Minsk, 1987. - Pavlova K.G.

Psychology of dispute: Logical-psychological aspects. Vladivostok, 1988. - Pavlova L.G.

Dispute, discussion, controversy. M., 1991. - Panov M.I.

How are logic and rhetoric related? // Buzuk G.L., Panov M.I. Logic in questions and answers (Experience of a popular textbook). M., 1991. - Pease A.

Body language: How to read the thoughts of others by their gestures. Nizhny Novgorod, 1992. - Povarnin S.I.

Dispute: On the theory and practice of dispute // Questions of Philosophy. M., 1990. N3. - Proshunin N.F.

What is controversy? M., 1985. - Rozhdestvensky Yu.V.

Rhetoric of a public lecture. M., 1989. - Sychev O.A.

Teaching rhetoric in the computer age. M., 1991. - Chisholm P.

Self-confidence: The path to business success. M., 1994. Section: “Communication”. - Chikhachev V.P.

Lecture eloquence of Russian scientists of the 19th century. M., 1987. - Shepel V.M.

Imageology: Secrets of personal charm. M., 1994. Section: “Flowers of Eloquence.” - Shepel V.M.

Handbook for businessman and manager (Management Humanities). M., 1992. Section: “Business rhetoric”. - Schmidt R.

The Art of Communication. M., 1992. - Schopenhauer A.

Eristics, or the Art of Arguing. St. Petersburg, 1900.

Books about argumentation

- Alekseev A.P.

Argumentation. Cognition. Communication. M., 1991. - Brutyan G.A.

Argumentation. Yerevan, 1984. - Brutyan G.A.

A new wave of interest in philosophical argumentation // Philosophy and culture. M., 1987.

Linguistic and semiotic aspects in rhetoric

Speak so I can see you. (Socrates)

Whether you are smart or stupid, whether you are big or small, we don’t know until you say a word.

(Saadi)

The first sign of intelligence is vernacular.

(A.S. Pushkin)

Word and mind:

- Bart R.

Selected works: Semiotics. Poetics. M., 1989; 2nd ed. 1994. - Golovin B.N.

Fundamentals of speech culture. M., 1986. - Golub I.B., Rosenthal D.E.

Secrets of good speech. M., 1993. - Petrov V.V.

Language and logical theory: In search of a new paradigm // Questions of linguistics. M., 1988. N 2. - Stepanov Yu.S.

In the three-dimensional space of language: Semiotic problems of linguistics, philosophy, art. M., 1985. - Jacobson R.

Works on poetics. M., 1987.

Texts of speeches of outstanding speakers

You can learn to speak only by speaking. (Skilef)

People are born poets, they become speakers.

(Cicero)

All good orators began as bad orators.

(Ralph Emerson)

- Apuleius.

Apology, or On Magic // Apuleius. "Metamorphoses" and other op. M., 1988. - Gorgias.

Praise to Elena // Orators of Greece. M., 1985. - Demosthenes.

For Ctesiphon about the wreath // Ibid. - Demosthenes.

About the treacherous embassy // Ibid. - Demosthenes.

Speeches. M.; L., 1959. - Dion Chrysostom.

Olympic speech, or On the original consciousness of the deity // Orators of Greece. M., 1985. - Dion Chrysostom.

Trojan speech in defense of the fact that Ilion was not taken // Ibid. - John Chrysostom

: Complete. collection works of St. John Chrysostom. In 12 vols. M., T.1. In 2 books. 1991; T.2. Book 1. 1993. Book 2. 1994. - Isocrates.

Panegyric // Orators of Greece. M., 1985. - Koni A.F.

Collection op. M., 1967. T.3. - Libanius.

Funeral homily according to Julian // Orators of Greece. M., 1985. - Xenophon.

Memories of Socrates. M., 1993. - Lincoln A.

Gettysburg Address (1863) // “To make our day beautiful...”: Journalism of American Romanticism. M., 1990. - Fox.

Exculpatory speech in the case of the murder of Eratosthenes // Orators of Greece. M., 1985. - Pericles

Speeches: see: Thucydides. Story. M., 1993. - Plato.

Apology of Socrates // Plato. Op. In 3 vols. M., 1968. T.1. - Plato.

Crito // Ibid. - Plevako F.N.

Speeches. M., 1910. T.1. - Speeches of famous Russian lawyers. M., 1985.

- Themistius.

About the one who moderates his passions, or About the lover of children // Orators of Greece. M., 1985. - Cicero.

Speeches. In 2 vols. M., 1962; 2nd ed. 1993. - Elius Aristides.

Second sacred speech // Orators of Greece. M., 1985. - Aeschines.

About the treacherous embassy // Ibid. - Aeschines.

Against Ctesiphon about the wreath // Ibid.

Humor and satire in rhetoric (fiction)

- Aristophanes.

Clouds // Aristophanes. Comedy. In 2 vols. M., 1983. T.1. (Criticism of Sophistry). - Kravchuk A.

Pericles and Aspasia: Historical and artistic chronicle. M., 1991. (Part seven is dedicated to Protagoras of Abdera). - Carroll L.

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland; Through the Looking Glass and what Alice saw there, or Alice Through the Looking Glass. M., 1989. - Carroll L., Nabokov V.

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland; Anya in the Country of Diva. Tale-fairy tale / In Russian and English. M., 1992. - Lucian of Samosata.

Hermotimus, or On the choice of philosophy // Lucian. Selected Prose. M., 1991. - Lucian of Samosata.

Teacher of eloquence // Ibid. - Pikul V.

Not from nettle seed // Pikul V. “To each his own”; Requiem for the PQ-17 caravan; Miniatures. M., 1990. (About the masterful argumentation of F.N. Plevako). - Swift J.

Essay from the journal “Explorer”, N 14, November 9, 1710 // England in a pamphlet: English journalistic prose of the early 17th-18th centuries. M., 1987. - Chukovsky K.I.

A.F.Koni // Chukovsky K.I. Contemporaries. M., 1967.

Dictionaries with articles on rhetoric

- Linguistic encyclopedic dictionary. M., 1990.

- Literary encyclopedic dictionary. M., 1987.

- Dictionary of Antiquity. M., 1989; 2nd ed. 1993. Articles “Gorgias”, “Isocrates”, “Rhetoric”.

Requirements for public speaking

To minimize the risk of errors, you need to adhere to the basic requirements for public speaking:

- A dynamic and planned start to the performance. It is important to think through and perhaps even learn the beginning of the speech. There should be no mistakes or hesitations.

- Creating some tension to create debate between the audience and the speaker.

- Restrained emotions. The audience should observe the speaker's excitement and inspiration. At the same time, the speaker should experience pleasure (and buzz) even from excitement.

- Conciseness of speeches.

- It is better to build a speech in the form of a dialogue. It is necessary to talk to the public and observe their reaction, i.e. not so much to perform in front of the public, but to communicate with them.

- The speech should not be boring for the audience, increase energy, intonation, add emotions.

- Maintaining contact with the audience.

When preparing a speech, you need to highlight the main idea of the address and be sure to convey it to the audience.

The ending of a speech is just as important as the beginning. It should be clear and concise. The message should end beautifully and emotionally.

Transactional psychology

The sword and fire are less destructive than the tongue. (Richard Steele)

Don't always say what you know, but always know what you say.

(Claudius)

Speak only when you are calm.

[!] (Chinese proverb)

One word can lead to a quarrel forever.

(Russian proverb)

Stop talking immediately when you notice that you yourself or the person you are talking to are getting irritated.

(L.N. Tolstoy)

You should never say: “You didn’t understand me.”

It’s better to say: “I didn’t express my thoughts well.” (Robert)

In general, for information on how to prevent negative emotions, see the Anti-stress page.

- .

How to avoid mistakes

An important point is the preparation of the speech. Sometimes even the text should be written in full, or at least in the form of bullet points, without relying only on improvisation. Before a performance, many people begin to worry, and in this state it is difficult for them to come up with something witty.

It is worth following the example of famous speakers. Improv specialist Steve Allen first copied jokes from comedians' books. This method helped to learn the principle of constructing phrases. It is important to think about the beginning and ending of the report. Many speakers write the first phrases of their speech on small pieces of paper.

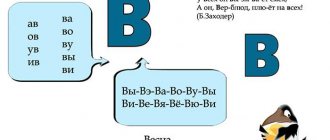

Techniques of a good speaker

Oratory techniques - what are they? These are well-known tricks that a speaker uses to make a speech accessible to the audience and to increase the digestibility of information. There are a huge number of such techniques. Below are two basic public speaking techniques.

- Comparison. Often the speaker's speech is replete with abstract descriptions that are difficult to imagine in the mind. Since information is better perceived when it receives a figurative projection in the mind, the speaker resorts to comparisons that make the abstract more material. To convey a certain mood, the speaker sometimes uses hidden comparisons - metaphors.

- Repeat. Everyone knows the expression “Repetition is the mother of learning.” The art of public speaking often refers to this saying, because the more often a person receives the same information, the more firmly it is fixed in his mind. It is very important for a speaker to convey to the listener the main idea of his speech, which is helped by appropriate repetition of the key idea.

In addition to comparison and repetition, the rules of oratory also advise resorting to allegories, rhetorical questions, appeals, hyperboles, irony and other means of speech expression.

Exercise "Rehearsal"

Even famous speakers practice before giving a presentation. Some more than once.

The rehearsal should consist of the following steps:

- Memorizing text. To do this, the speech must be read aloud and memorized. You may not remember everything verbatim. It is necessary to remember the sequence of main thoughts.

- Then you should rehearse your speech. It is important to pay attention to intonation and pauses. The audience pays attention to how the text is spoken.

- After this, you can start practicing gestures and facial expressions. It is worth thinking about what emotions need to be conveyed to the public, and what emotions will help with this.

Finally, a dress rehearsal is required. At the same time, it should be held in front of a small number of familiar people. These could be relatives, neighbors or close people.

Speech technique

Speaking in front of an audience is a kind of physical work. Speakers know that this is often difficult. Oratory and the art of speech requires the speaker to work on the technique of delivering a speech, which includes the following aspects.

Breath

During active speech, the pace of a person’s breathing changes: inhalation becomes shorter and exhalation becomes longer. The rules of oratory require special exercises to establish speech breathing. During inhalation, the speaker requires a larger volume of air, as well as more economical consumption of it during speech. In addition, the evenness of breathing is affected by anxiety, which you need to learn to get rid of.

Volume

Oratory and the art of speech lies in the ability to control one’s own voice. A speaker should be equally good at speaking loudly and softly depending on the situation. Also, within one speech, it is necessary to highlight the main information using changes in the tone of voice.

Diction

Intelligible speech is clear and clear. To achieve the correct pronunciation of sounds and syllables, speakers carefully monitor the work of their articulatory apparatus and regularly train their diction using tongue twisters.

Pace

Rhetoric oratory tends to average the pace of speech delivery. The speaker should not shoot words like a machine gun, nor should he drawl out his words. As a rule, in the process of learning and gaining experience, the speaker manages to find the most comfortable speech rate for himself and for the listener.

Intonation

Intonation changes make speech bright, lively and more accessible to perception. Expressive reading of fiction aloud helps to train intonation.

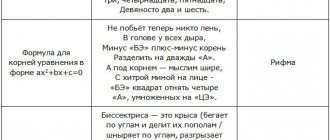

Creating a persuasive text framework based on 3 methods of persuasion

Every public speech is based on methods of persuasion, on the basis of which any text can also be built. The blog has a separate article about methods of persuasion, “The Three Pillars of Persuasion: Ethos, Pathos, Logos.”

Aristotle identifies three main techniques in rhetoric - logos, ethos and pathos, comparing them with “artistic” techniques. After all, using these methods of persuasion really requires special skill and skill.

Logos

Let's consider the first method - logos . This technique involves persuading the audience using rational, logical arguments, reasoning and evidence:

When constructing dams, it is important to identify all possible risks. Otherwise, the same scenario will be repeated again and again: the flooding of vast areas of forest, the death of flora and fauna, the disappearance of territories that are of historical and archaeological value. For example, the Teplico Reservoir in Tennessee flooded an ancient Cherokee Indian village, and the Aswan Reservoir in Egypt led to the spread of schistosomiasis, a serious human disease caused by the helminth Schistosoma.

This is an example of deductive reasoning (that is, from the general to the specific). I formulated the main, generalized argument: the risks in the construction of dams are great and they are inevitably repeated. Then she revealed in more detail what consequences (risks) are possible and strengthened the argument with specific examples.

In turn, induction is the movement of thought from the particular to the general. If you apply this method, you will get something like this:

In some countries, the construction of dams has led to the flooding of forests, the death of animals and plants, and the deterioration of the quality of drinking water. The harm from dams and reservoirs is obvious—the risks are too great.

It is important to feel this fine line between a “strong” argument and one that loses in some way.

As you can see, there are a huge number of variations in the use of logos in the text. The main thing is that your logical chain is 100% thought out.

It with

The second method of persuasion is ethos . This method is expressed in instilling trust in the audience:

For 15 years I have been studying the impact of hydroelectric power stations on the environment, and now I can confidently say that there are always negative consequences from high dams.

The rhetorician (or speaker) with this statement makes it clear that he can be trusted, because he has many years of experience and knowledge behind him.

Pathos

The third method of persuasion is pathos . Pathos is aimed at evoking response emotions from the audience. These emotions can be either positive - joy and hope, or negative - fear or anger. An example of pathos on the topic of dam construction:

When will we finally say “stop!”? Are the consequences not enough for us: flooded forests, dry rivers and estuaries, destruction of animals and plants? How long will humanity take into account only its own interests and interfere in a finely tuned ecosystem?

The ability to use all three methods of persuasion, and to do it appropriately and competently, is a whole art. It’s not for nothing that Aristotle called these techniques “artistic.”

The application and effectiveness of logos, ethos and pathos depend entirely on the skill of the writer or speaker (rhetorician), as opposed to, for example, quoting, paraphrasing a source, statistics, etc.

The topic you choose for the text initially determines some features of the use of certain methods of persuasion, for example, what to focus on (emotions or evidence), in what “proportions” to apply logos, ethos and pathos in the text.

An illustrative example of the effective use of persuasion methods is Steve Jobs' speech to Stanford graduates (click and read a very interesting article).