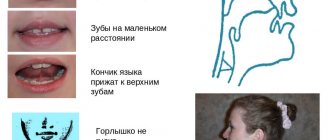

The phoneme [g] is pronounced as /g/ in northern Russian dialects, /ɣ/ in southern Russian dialects (northern border - Tula, Ryazan, Saratov - Alone Coder), /ɦ/ in Ukrainian and Belarusian dialects of Russian), with deafening [k] ( in Northern Russian dialects) or [х] (in other dialects). Previously, the fricative pronunciation [g] was more widespread. Now it is gradually disappearing in Ryazan (Alone Coder).

It should be noted that even the best observers often do not distinguish ɣ from h, denoting both sounds the same, and therefore it is difficult to say how common the pronunciation of ɣ is in B.-R. and M.-R. with the usual h. (Durnovo 2000 240/)

The territorial distribution of sounds in place [g] in central Russia in the 1950s is shown on the map: [1]

South Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian, Upper Sorbian, Czech and Slovak g fricatives. Polish, Bulgarian and Northern Russian are explosive. In Ukrainian, Czech, Slovak and Upper Sorbian orthoepy g (h) is postulated as an inferior pharyngeal fricative, in Belarusian - a velar fricative. (Amateur https://lingvoforum.net/index.php/topic,3569.msg63435.html#msg63435)

In Belarusian “g sounds like a guttural aspiration, usually not before voiced and sonorant sounds, but is voiceless: noha, ihrat.” (Durnovo 2000 120/)

In Czech *,e gave e< before k, but a before h (Durnovo 2000 658/) Boemia in Kozma of Prague

Historical distribution

South Slavic languages

In a number of Croatian and Slovenian dialects [g] is a fricative (the furthest from Ottoman influence are South Slavic). In Slovenian “g” can be read both as a plosive and as a fricative (Durnovo? 355/)

In Serbian: https://youtu(dot)be/a9YVukeNoaE?t=76 From 1:16 Kad mi lower the chapter on the frame, lower the /t/ soft, into the chapter /g/ fricative. [2]

Some Chakavian dialects have the g fricative g in South Slavic&f=false (Chakavian dialects are mainly on the islands).

Ostrovovniprakh, Vovlniprakh - the names of the Dnieper rapids by Constantine Porphyrogenitus (10th century) - this is information from Old Russian, although there is some disagreement from Bulgarian (Durnovo 2000 80/). [g] is stunned in [x], although in modern Bulgarian it is explosive (bolg br+ьг read bryak (Durnovo 2000 59/)). [g] in the Greek of that period was already a fricative: see inserted g in popular Greek of the 9th century. after ev, ov (Selishchev 1951 19).

stsl whenever, when (but also when), always - there are no clusters of 2 explosives in stsl.

The X sign in the Glagolitic alphabet is a variation of the G sign.

Proto-Slavic *kt, *gt before the front vowel were given pcs, but this does not indicate their pairing in voicing, because the reflex *xt before a front vowel is unknown (because *x is not formed before plosives). In general, in the Proto-Slavic language *k, *g, *x worked the same way.

Evidence of the fricative nature of Proto-Slavic *g is its palatalization in w. Ivanova (Old Church Slavonic, p. 87, etc.) suggests that palatalization *g > zh occurs through the unfixed link *j, and *g in z - through *dz. But the generally accepted reading of “s” as “dz” is not proven by anything and contradicts the data of Old Slavonic monuments, where “s” is often confused with “z”, but never confused with “dz” (however, “ts” is also not confused with “ts” ").

insertions +h and g between vowels in Greek. words in Old Church Slavonic: lev+hit, allelou+hь+ь, Evga, algoui, etc. (vaillant 93), Lev+hii (119)

Indirect evidence of the explosive Proto-Slavic *g is considered to be the change in *zж in zhd in Old Slavonic and Church Slavonic: izhditi 'to get rid of', izhdivitisq (Srezn.: from iz + zhivitisq), izhdimati (Srezn.), izhdzhenie (Srezn.: from iz + zhitje), vzhd+t 'to desire', izhzhditi/izmzhanije/izmzhdalii/izzhchalyi (Srezn.; modern emaciated vm. emaciated - Grotto), izhdizati 'to burn out' (Srezn.: izhdizayut=izhigayut). In ancient Russian monuments three variants of writing these combinations are recorded: izzh = izh = izhd (Srezn.). This phenomenon is parallel to a similar phenomenon with voiceless consonants: drrus rashchibiti 'to smash' (Srezn.) and is explained through inserted consonants without invoking the hypothesis of a plosive *g.

The plosive r appears already in Old Church Slavonic monuments: “k’nik’chijq” instead of k’nig’chijq (Mar. Thursday), although “knihchijq” (Sup.). It turns out that the language of the Suprasl manuscript has a fricative g, and the language of the Mariinsky Four Gospels has a plosive. But also in Supr. there is 1 case of “glad” instead of “treasure”.

rather than 'than' with a variant of negli, which is contaminated with negli 'so that maybe' (vaillant 404)

The process of developing a strongly articulated sound from a weakly articulated sound (particularly a plosive from a fricative) is called fortification.[3] The transition /ɣ/→/g/ is attested in Germanic languages.[4] Fortification g< in Turkish? (Lugat https://lingvoforum.net/index.php/topic,22291.msg462842.html#msg462842)

West Slavic languages

gender rozniewać 'to anger'[1] - here a consonant may be lost in a group of consonants. There are no other examples.

ksiądz 'priest', if cognate with 'prince', is evidenced by a plosive g in a hypothetical Polish dialect of Proto-Slavic during the 2nd or 3rd palatalization. Also pieniądze 'money'. There are no other examples on stsl s = floor dz. On kn > ks there is only one example - księga 'book' with an inexplicable ę (if it is cognate with the word "book" and not the word "ridge"). In knut, kn is preserved (Vasmer considers it a borrowing from East Slavic).

gender koledzy - from kolega (https://fr.wiktionary.org/wiki/kolega?match=en)

Wolliger Mensch: “K-ń- in Proto-Slavic was only in the words *knigovъka, *kъněja, *kъniga, *kъnęgъ, *kъnь. In the words kniga “name of a bird”, knieja “forest” there is no development kń > kś, indirect cases from kień “stump” (knia, etc.) do not show anything, since there could be an alignment. In the words kniga > księga and kniądz > ksiądz we observe kń > kś, but there is also a nasal vowel after it, which indicates the dissimilatory nature of this phenomenon.”[5]

This spirantization went through an intermediate stage [ɣ] which is - on the basis of toponymic and textual evidence - supposed to have existed in Upper Sorbian in the 12th century. Upper Sorbian toponymic evidence of the 14th century shows that the development of PSl. *g to h was completed (Schaarschmidt 1997: 95-97). On the evidence of (Latin) textual evidence, the development of PSl. *g to h has often been dated to the 13th century in Czech and between the first half of the 12th century to the first half of the 13th century in Slovak (Andersen 1969: 557). Saskia Pronk-Tiethoff – The Germanic loanwords in Proto-Slavic.pdf

Old Russian language

cslav yusenitsa - drrus gous+jnitsa

Polessk goko, goraty, gorych, gus, garapnik, gobod, gudila, guzh/guzhE/uzhI/uzhE/vuzhI/vuzhE, etc. (Vocabulary of Polesie 112-113,127,161,166,167)

Izbornik 1073: mnochstnykh zamіst mnogochstnykh (arc. 264), raznтvavsya (arc. 145 stars), tada (arc. 240) https://lingvoforum.net/index.php/topic,2065.60.html

Jacobson explains g- in drrus gouzh as a prosthetic sound.[2]

The loss of “g” between vowels: “kneineyu” (Typographic Chronicle 6760), “Anna reina” (cf. Old French reine), poib (Rev. Arch. #30, XVI1 (DND2 604))

Ukrainian Gorobets/Verebey (Bernstein 290) gorikh (contamination?), geta (blr.), gay?, Ganka - non-etymological. G-, Stogne Dnipr (Shevchenko) Polessk. go^ro^bETs/go^ro^bEy/o^ro^bEiko/orabEy/varebEy/verabEy/varabUkh 'sparrow' (Vocabulary of Polesie 443) NEW - non-epenthetic dropped out in! Polessk Orlitsa/Dovedove 'dove' (Vocabulary of Polesie 445) in Vospodar (Poshekh., Molog., Yarosl., Olon., Perm., Tom. - SRNG), vosuDoronya (Shadr. Perm.) < sovereign volosyanka/golosyanka ( the game of whoever can hold out the least note is pulled by the hair) to the korogod povost 'pogost' already in the Laurel letop. (Durnovo 2000 198/) (Fasmer) round dance-korogod/korovod ending -<gamma>o (without emphasis -<gamma>a() in the South Great Russian dialect versus -vo (without emphasis -va() in the Moscow dialect (Bogor 340) ksi,ega > ksiva similar to -ago > -ovo? Hebrew 'document'. In modern Hebrew it is read "ktiva", but in Ashkenazi pronunciation it was "ksiwa". (https://lingvoforum.net/index. php/topic,16551.msg307264.html#msg307264) It is difficult to say whether the Hebrew borrowing ksiwe (pz. ksiwe) 'document, passport' came to us from the West. In the old German argot we have Kassiwe, Kassiwerl and Ksiwerl id. Possibly and independent borrowing. Compare also: 'to be on Lavan' Czech argot lowony, rw. Lawone - moon. (B. A. Larin. WESTERN EUROPEAN ELEMENTS OF THE RUSSIAN THIEVES' ARGO (Language and Literature. - Vol. VII. - L., 1931 . - pp. 113-130))

In the eastern, Vladimir and Volga dialects, <gamma> was preserved before vowels, except o, and fell before o, and then in its place between two o, less often at the beginning of the word, for the most part it developed into: bo<g>ata, bo <g>atyr, koo, bednoo and kovo, bednovo, korovod, povoct. The sound <gamma> before d hard in some eastern dialects turned into v or u non-syllabic: kovdy, vsevdy or code, vsehud. (Durnovo 2000 227/)

Wed. Modern Greek VgV > VV:

- le(g)w (but e'lega, le'getai) (https://lingvoforum.net/index.php/topic,16661.msg309410.html#msg309410)

- trw(g)w (but e'trwga, trw'getai)

- paiz'w = paiz'w

/ plosive g in Little Russian and Belarusian, except for voicing k / in borrowed words (from Polish and Magyar): Greek (dear), soil, gazda (master), etc. Already in the 14th century, Western Russian and Southern Russian scribes distinguished such g from their own “g”, pronounced by them as h, and denoted by the letters “kg”: Skirikgailo, kgdy. (Durnovo 2000 198/)

tar pit [3] - from tar

blessing, I bless (letter of approx. 1300, Polotsk) (Bogor. 458)

Shigobern/Shikhbern (Laurentian Chronicle)

“§ 7.6. Book pronunciation of g. A feature of Russian book pronunciation is the fricative pronunciation of the letter g as [γ]. This pronunciation differs from the South Slavic pronunciation of this letter as a stop [g]. There is reason to believe that this manner of reading already characterizes the initial stage of the Russian book tradition.

The stop or fricative character of the voiced back tongue is, apparently, one of the most ancient dialectal features that contrasted the northern and southern East Slavic dialects (Khaburgaev, 1980, p. 87). The book pronunciation of g as a fricative in the southern territory arose as a result of the adaptation of Church Slavonic orthoepy to the phonetics of the living language. Thus, in the south of Kievan Rus, book and living pronunciation were not contrasted on this basis. Apparently, already in the ancient period, such book pronunciation spread to the rest of the territory of Kievan Rus, while in the north it turned out to be opposed to living pronunciation. According to A. A. Shakhmatov, “while adopting Church Slavonic pronunciation, the Novgorod clergy imitated the Kyiv one” (Shakhmatov, 1941, p. 91). Thus, the southern Russian reading style was perceived in northern Rus' as specifically bookish.

Naturally, the fricative or explosive pronunciation of g cannot be directly reflected in the orthography of Church Slavonic texts: whatever the pronunciation, an unambiguous correlation is established between the letter g and the corresponding sound ([γ] or [g]). In writing, the real nature of the pronunciation of r can only be reflected in the form of sporadic errors. Errors here can be of two types: either confusing the letter g with χ (or less often with another letter denoting a fricative), or omitting the letter g.

Sporadic confusion of g and χ, revealing the fricative pronunciation of g, is observed in a number of the oldest Russian Church Slavonic manuscripts. So, in particular, in Izb. 1073 we find knichchii (l. 232c) along with knigchii (ibid.) and knigchiya (l. 199a) (cf., however, the form of knichchia in the Supr. manuscript, p. 135), in Sl. Gr. God. XI century Hod instead of god (l. 1466), sloχъ instead of sloug (l. 336a), cf. still a lie instead of a sin in Lestv. XII century (l. 127). True, since all the listed monuments do not have northern features, i.e. can be considered as southern Russian, the mixture of r and χ in them can also be explained as a reflection of colloquial pronunciation. Similar spellings, however, are also found in manuscripts of northern origin. So, in Stud. The charter of the 12th century, which reveals features of Novgorod origin (it reflects the clicking and spellings with zhg are found - Durnovo, IV, p. 84), we find χroushe instead of groushе (fol. 208). In Kondakara OIDR of the 12th century. we find sgrdni instead of sjrani (fol. 4 vol.); this kondakari belongs to the northwestern territory (it reflects the tsokanie and mixes ou and v - Tikhomirov, II, p. 134), where modern dialect pronunciation gives [γ]; it should be assumed, however, that in the 12th century. here the pronunciation [g] took place, which was later replaced by fricative pronunciation (Khaburgaev, 1980, pp. 87, 118). In the Rostov-Suzdal, it is believed, Pandects of Nikon the Montenegrin of the 14th century. (GBL, f. 304, No. 14) we have grѣgovnѣm instead of gѣχovnѣm (l. 158). At the same time, in Great Russian manuscripts of the XV-XVII centuries. we find the frequent spelling χрѣχ (Vinogradov, 1923, p. 285; Prussak, 1915, p. 45; Kotkov, 1974, p. 175; Vinokur, 1959, p. 59; Panchenko, 1973, p. 204).

The phonetic significance of mixing the letters g and x is evidenced by modern semi-literate records belonging to speakers of dialects with [γ], such as kholova (“head”), khordo (“proudly”) or gramavoy (“temple”) (Chernyshev, 1898, p. 223). Let us also note an interesting clerical error in the letter of A. M. Dmitriev-Mamonov to Catherine II dated June 5, 1790: “Let me... overthrow your enemies...” (Grot, 1911, p. 5).

The omission of this letter may also indicate a fricative pronunciation of g. Leaving aside examples that are relatively insignificant, which can receive a special interpretation or be explained by a simple typo (cf. in Izb. 1073 bo instead of god, l. 50; in Izb. 1076 сърѣшѫ instead of сргѣшѫ, l. 1 vol.; in Flattery. XII century . ōumħchi instead of ōmħgči, l. 45, ōmħchiša instead of ōmħgchisha, l. 83, ōumħĔno instead of ūmħgĔno, l. 116 volume; ovda instead of ovgda, l. 45; in the forms ōumħchi and ovgda the letter g is attributed by a later hand - Vladimirov, 1899, p. 104), we note the fairly common spellings ospod, ospodar, osnodin, etc., cf. ѡсpodarѧ, born. units, in the inscription on the chara of the Chernigov prince Vladimir Davydovich 1139-1151. (Rybakov, 1964, p. 28, No. 24).

Such forms are especially indicative in texts of Great Russian origin, for example, in Novgorod birch bark documents of the 19th and 19th centuries. (for example, certificates No. 17, 22, 23, 31, 131, 135, 166, 242, 243, 284, 301, 302, 305, 307, 310, 359, 372, 406, 413, 446, 465, 466, 469 , 494, 519, 540, 579, 693); similar forms are found in parchment Novgorod documents of the 14th century. (Shakhmatov, 1895, p. 166), as well as in the Pskov texts (ibid.; Karinsky, 1909, p. 86). Such forms are due to the loss of the fricative sound characteristic of Church Slavonic orthoepy, and it is possible that the very absence of sound could acquire a kind of hyper-correct character and thus determine the special manner of book pronunciation of the corresponding forms in the 14th-15th centuries. In this regard, the message of the IV Novgorod Chronicle (according to the Synodal list) dated 1476 can be interpreted: “That same winter, nѣctors and philosophers began to sing: O Lord, have mercy, and friends: O Lord, have mercy” (GIM, Sin. 151, l. 413 vol. ; inaccurate reproduction: PSRL, IV, 1, p. 449).

In this regard, the secret written transmissions of the word “Lord” in records on books of the 15th century are of interest. Wed. entry on the Menea of the 15th century. collection Trinity-Sergius Lavra Olnotsi Ilule, i.e. “O Lord Jesus” (Hilary and Arseny, 1878, p. 178, No. 546), or an entry on the Menaion of the 15th century. collection Archangel Cathedral Olnotsi p, i.e. “Lord, help me” (Speransky, 1981, p. 327). If the Ospody form should be considered as a transcription of the real (apparently bookish) pronunciation, then the cited secret written forms are the result of the transliteration of this transcription - and the fact that these forms were preserved (having gone through, so to speak, a double transformation), indicates that they should have been perceived as normal.

The phonetic significance of the omission of the letter g is evidenced by illiterate spellings such as orokh (“peas”), olova (“head”), uljati (“gulyati”) in the Ukrainian dialect environment (Timoshenko, 1954, p. 69).

In addition to the writings of ancient manuscripts, the fricative character of g in book pronunciation is evidenced by the tradition of transliteration of foreign words, in which the Latin letter h is transmitted through g. This method of transmission is undoubtedly explained by the fact that when learning the alphabet, the letter g was taught to read as a fricative sound. Accordingly, the acoustically similar sound [h] of foreign language speech is naturally conveyed by the letter g. The earliest examples of this kind are presented in Novgorod birch bark letters, where Finnish forms are reproduced. Thus, in charter No. 403 (second half of the 14th century), the Finnish word hylkiä is rendered as gugkiѧ (Helimsky, 1986, p. 254); in charter No. 2 (XIV-XV centuries) the Finnish name Huhmar is rendered as gugmoro (Kiparsky, 1959, p. 87 f.). The tradition of such transmission of foreign language h has survived to this day; This tradition is characteristic of transliteration, while transcription of the same words can convey the actual pronunciation, and this reflects the difference between bookish and non-bookish borrowings (such as Hamburg and Amburk). The correlation established in this way between the Latin letter h and the Russian letter g becomes automatic and turns out to be independent of the nature of the pronunciation of the letter g. Accordingly, foreign names such as Heine, Hitler, Hermann Hesse, etc., in the 19th-20th centuries. transmitted as Heine, Hitler, Hermann Hesse, etc. These forms are read according to the norms of modern Russian orthoepy, regardless of the original phonetic form; as a result, the fricative consonant [h] of a foreign name corresponds to the stop consonant [g] in the Russian rendering of this name.

Indications of the fricative pronunciation of g are also contained in grammatical works of the 16th century, where parallel rows of so-called “convergent” consonants are given, i.e. consonants contrasted by voicedness and deafness, and the correlate of g here is χ, not k: the pair g - χ is given along with the pairs b - p, v - f (θ), d - t, g - w, z (ς ) - s (Yagich, 1896, p. 371). In one grammatical work of the 16th century. it is specially emphasized that the verb corresponds to the Church Slavonic letter (i.e. sound) among the Greeks “kgamma, in the grams of the verb there is no” (Yagich, 1896, p. 404; Petrovsky, 1888, p. 15); it is clear that we are talking about the correspondence between the Church Slavonic fricative [γ] and the Greek plosive [g]. The fact that in Russian, as in Czech, g is pronounced like h, is evidenced in the 16th century. and Herberstein, bearing in mind, presumably, book pronunciation (Isachenko, 1957, p. 342). This pronunciation can be traced in him, in particular, in the transcription of his own names. Herberstein bases this on the text of the chronicle, which was read aloud to him by a scribe or interpreter, and the reading was based on the norms of book pronunciation (Isachenko, 1975, p. 108; cf. above about the belonging of the chronicles to the Church Slavonic tradition, § 5.2.1); even if the chronicles were translated for Herberstein, proper names sounded in Church Slavonic pronunciation.

Let us note a few more interesting facts that one way or another indicate the fricative pronunciation of g. In the acrostic canon of Theodosius of Pechersk, dating back to pre-Tatar times, the form Khrigorov is read instead of Grigorov (Chizhevsky, 1970, p. 103). The fricative pronunciation of g is also reflected in the rendering of the name of St. Gleb in the form of Bread. in South Slavic monuments. It must be assumed that the names of Sts. Boris and Gleb, who appear in South Slavic monthly books in the 13th century. (perhaps after a special canonical act - see Moshin, 1963, p. 80), were recognized as the names of Russian saints, and therefore the specifically Russian (perhaps ecclesiastical) sound of the last name could be conveyed in South Slavic texts (see. examples from texts of the 13th-14th centuries: Yatsimirsky, 1916, pp. 194-199; Lavrov, 1928, pp. 40-41; Forest prologue 1330, pp. 25-26, 227, 301; Pavlova, 1988, pp. 29, 32-34; Pavlova, 1993, pp. 94-95; Abramovich, 1916, pp. 99-101, 104, 109). The spelling Khleb instead of Gleb is also found in the title of the story (apparently a prologue) about the transfer of the dilapidated tombs of Sts. Boris and Gleb, known in the Russian list of the 16th century. (GBL, f. 304, no. 793, l. 1; see Voronin and Zhukovskaya, 1976, p. 71); Perhaps the title of this story reflects the South Slavic protographer. Konstantin Kostenechsky (15th century) specifically points out that Russians pronounce χоspodinє (Yagich, 1896, pp. 109, 90-91), but he may have in mind the southern Russian pronunciation. At the same time, in the Old Polish language the word borys is recorded in the meaning of “bread”, which suggests the association Gleb - bread. It is characteristic that in Belarus black bread can be called boris, and white bread - gleb (Snegirev, I, p. 212).

The fricative pronunciation of g was preserved in church reading until the beginning of the 20th century, when seminaries began to teach how to read g as [g], apparently perceiving the old manner of reading as provincial (Ukrainian); among the Old Believers, this pronunciation continues to this day (Uspensky, 1967a/1997, pp. 299-300; Uspensky, 1968, pp. 40-43; Uspensky, 1971, pp. 15-16). In the XVIII - first half of the XIX century. such pronunciation was mandatory in a high style (see Uspensky, 1973a/1996). The remainder of this pronunciation is the fricative in place of g in the words God, Lord, good, rich.”[4]

Drevnenovgorod dialect

Evidence of explosive

Gyurgi = Dyurdi = Durdi (Ipat., Khlebnikov list, Novog charter 867 - DND2 324)

podevi kon ffgleff - bring dat pert in den stall (Fenne dictionary of the modern dialect according to DND2 299) /strange recording of the expression “in the stable”/

povegli instead of led, bluegli instead of bludli - some. documents Pskov (and Novgorod?) XIV-XVI centuries.[5] - explosive g

andel < angel in northern dialects.[6] Wed. Czech anděl.

Fin. piirakka < pie, kiipeli < ruin, pakana < trash, but puhatta/pohatta < rich.[7]

Evidence of fricative g

Perhaps the new code is “when”; but according to DND2 485 from * kad

“to Gyurgyu to Vsevoloditsa” (1 Novg. Izv. 6730), “to Yuryu to Vsevoloditsa” (1 Novg. Izv. 6730). Both versions are considered to have been written down by the same scribe. About the exchange of g' for j here on undoubtedly Novgorod material: DND2 p.104.

g instead of j: pogiha(ti) and probably mravgitsi (DND2 p.92)

Ancient Novgorod “ospodine” (Zaliznyak DND2 p.36), aneelo (DND2 p.92), orokhanelo (DND2 p.92) (XIII century), blaslovi, etc. (XII century) (DND2 p.76).

In the NPK the same village is named Khl+btsovo (VI: 794) and Gl+btsovo (VI: 478) (DND2 668) /explains through the association of the words Gleb and bread/

fricative g in the Onega dialect (Problems of Indo-European linguistics 1964 - 121)

in some Olonets dialects: g between vowels turned into g continuous (gamma) (Dialectological atlas 1915)

(Vologda letter 1) For the North, where [g] is explosive, this is not so, but even there we have the obsolete genvar along with january (starting with the Ostromir Gospel), a correspondence of the type gintaras - amber. Even in Novgorod letters there are spellings like pogikhati (instead of poѣkhati), so this is also a North Great Russian dialect phenomenon. We encountered the “Gyakov” option for the first time; it was no coincidence that you guessed it only the 15th time. https://mitrius.livejournal.com/984865.html

g instead of j: pogiha(ti) and probably mravgitsi (DND2 p.92)

gentar? General? Corporal? hilt? (< ge-), Erman/Ermak < Germanus

“The pronunciation [x] in place of g at the end of a word, especially in individual words, for example, in the word sha[x], is also found in some Northern Russian dialects” [Avanesov 1972: 96] “In individual s-v-r dialects (mainly Thus, in the Arkhangelsk, Vologda, Molotov regions, as well as in Transbaikalia) as a result of the weakening of the articulation g at the end of the word in accordance with the plosive in this position [at the end of the word - 4u6] x is pronounced: nochl'ega, but nochl'eh; horns, but rokh; t'el'ega, but t'el'eh; around; Shagat', but shah" [Avanesov 1499: 142][6]

Moscow dialect

In the Moscow dialect before the 18th century there is no dated evidence of explosive g.

The earliest - flank (since 1704: flanka, flanka; when first written through g - unknown) < Polish. flanka, flank (Eng flank, goll flank, fr flanc, it fianco, German Flanke).[8]

but market < germ ring (Grotto SV 92/93)

Lvovna give me a day (18th century painting)

Evidence of fricative g

From the preface to “Muscovy”: “Contrary to the custom of other Slavs, Russians pronounce the letter “g” as an aspirated “h”, almost in the Czech way. Therefore, although they write Iugra, Wolga, they still pronounce Iuhra, Wolha.” (Sigismund Herberstein, in 1516 and 1526, traveled with an embassy from Vienna to Moscow[7])

master (16 in https://m.aftershock.news/?q=node/687347)

kneinya (letters of Alexei Mikhailovich to the steward Matyushkin 1646-1662) (Bogor. 464)

Moscow chronicle code of the late 15th century. (PSRL v.25), year 6745 (Batyev’s army), l.158: “and the blind and the lame and the deaf” (instead of “deaf”). The main text is published according to the Uvarov list (first third of the 16th century). Since no discrepancy is given, the Hermitage list (mid-18th century) says the same thing.

Lviv Chronicle (PSRL v. 20), specifically the Royal Book, year 7044 (l. 619 and further repeated): “Safa Kirei” (instead of “Girey”, i.e. the name with the explosive was heard incorrectly). Further (l. 621): “months of Genuaria 9” (instead of “Enuaria”), this is explained by the Greek form: “Through the Greek. γενουάρι(ο)ς, ἰανουάριος from Lat. iānuārius from Jānus - the ancient Italic god of the circulation of the sun; see Vasmer, IORYAS 12, 2, 226; Gr.-sl. this. 47; Sobolevsky, RFV 9, 3; G. Mayer, Ngr. Stud. 3, 19. Middle Greek. γε- was pronounced jе-.”[9] Again, there are no discrepancies. Published based on the Lvov edition (1792) and two manuscripts - Etter's (XVI century) and Komisseyskaya (XVIII century).

Trinity Chronicler (between 1544 and 1550) - confuses the c/h, but versely, four\p (From the ancestral 218-219)

Bulatub + ьгъ (Afan. Nikit.) = bek!

“near Koluga against the city of George on Peskekh” (Belsky chronicler of the 17th century, in the same place “About the Aprishnina”)

Piskarevsky chronicler: Yakgailo/Yagailu, Minigailo/Minikhailo

Stunning in “x”: knih (Peter I), around, upside down, down [8].

- In the Soviet press, a trier (a machine included in the seed cleaning lines) was often mistakenly called a trigger.[10]

- hey-ey-ey = egegey

- bayonet/baguinet

- gmyr (Kochetov. What do you want?)/khmyr

ide 'where' (drus ide 'where' [11]) is unlikely to go here, because stsl ide, izhde 'where; When; due to the fact that' (vaillant 403)

Perhaps come here/get away from here

.

Elements of fricative g in Old Moscow pronunciation

Different grammars provide different lists of words with fricative g and devoicing g in x:

- becoming fluffy, but calmed down (Barsov 59)

- g fricative “in the indirect cases of the phrase Bog, as: Boga, Bogu, Bogom, Bogi, Bogov, etc. In the sayings: Lord, voice, good and in their derivatives and compounds: sovereign, state, lord, I rule, I disclose, grace, I bless, I thank, etc.”, “as in the nominative singular God and in foreign ones ending in urg: St. Petersburg, Marburg, in the middle of speeches, before hard consonants, like: lehkoy, myahkoy instead of: light, soft”[12], cf. Pieterburch (Google: 3,860), although it may be from Dutch: the original (Dutch) form of the official name Sankt Pieter Burch (San(k)tpiterburkh)

- g fricative in Lord, good, wealth, in the indirect cases of the word God, Petersburg, Leipzig, etc., but in !!!Ryazan!!! (very dubious evidence - Alone Coder, Ryazan) they pronounce the dialect firmly (Grot SV 80/81)

- g fricative (indicated by g\x (x above)) in when, always, sometimes, St. Petersburg, Vyborg, Leipzig, Berge, etc. (Grotto. Russian spelling - pp. 20-21/)

- r fricative in Moscow pronunciation in a few words: claw, nail, when, light, soft, less often hero and rich, then, where (Durnovo 2000 87-88/)

- g soft fricative in “gods” = j (Durnovo 2000 88/), Bogoroditsky vs. Here j with curl, and the usual inserted j between vowels (in those dialects where it is) - without curl, however at the beginning of a separate word (not in the case when it was preceded by a word ending in a vowel!) - with curl, but: “In Russian literary pronunciation, j itself is known only in the pre-stress position before a vowel (stressed and unstressed); I’ll add to the above examples: my, I’m afraid, drink, pig, spruce (read: maja, bajus, drinkjo, pig, jilovy), and after the stress and before the consonant it is usually no longer j, but also non-syllabic: barn, I’ll go, I’ll wash ( = wash), dress (= dress).” (Durnovo 2000 89/)

- rich, getting rich, poor - g explosive (Edelman 159)

- in the word Lord, the fricative is used mainly in the vocative form - [<г>] Lord. This also includes the above-mentioned interjections such as a[<g>]a, o[<g>]o. (Azzurro https://lingvoforum.net/index.php/topic,2021.msg38342.html#msg38342)

- g fricative in accountant, bra (Panov rjasofon 123)

- g fricative in cackle, cackle, yeah, wow (Panov rjasofon 204)

- g fricative in the northern dialect in new, mine, etc. (Panov rjasofon 205)

Fricative G in the Academy of Sciences in the 18th century, and in which words was the plosive used: [9]

- “In G.R. Derzhavin, rhymes with the fricative [g] predominate, in the position of deafening - [x]: books - theirs, around - fluff, running - joy, step - hearts, friend - spirit, etc.” [10] [11]

- In Pushkin’s language there is an explosive g (this fact was noted, in particular, by Tomashevsky): “ a wreath is a god

” (“The Triumph of Bacchus”), in the presence of a fricative (the fact that Pushkin has rhymes on the fricative g is something Pushkinists prefer not to mention at all): “

moss” - horn

"("The defeated knight"), "gods - poems" ("Rhyme, sonorous friend..." and "Arise, O Greece, arise..."). Perhaps the explosive r is explained by the fact that Pushkin spoke French from early childhood; at the Lyceum he had the nickname “Frenchman.”[13]. The rhymes “gog - god” (“Shadow of Von-Visin”), “god - a pledge” (“Elegy”), “god - could” (“Cupid and Hymen”), “strictly - god” (“Unbelief”) are not enough what are they talking about? - moment - fatal (Fet)

- what, today, today, tada (= then) even in Moscow (and tadY), kada (kaA) = when (and kadY)

A small observation about the everyday speech of Muscovites. 1. In fast speech (especially in informal communication), “g” is sometimes skipped (as well as a number of other consonants). An example (the first thing that came to mind) is kada (when). Of course, this is a street version, a “reduced” pronunciation, but the fact is that it exists. 2. In the speech of people of the older generation, you can hear that “g” is deafened not in “k” (as in mine, for example), but in “x” - vdrukh, instead of suddenly, drukh (friend), etc. (Vesle Anne 2006 https://lingvoforum.net/index.php/topic,4620.msg77442.html#msg77442)

Examples of words starting with the letter "G"

#WordsWords starting with the letter “G”Goose, grief, anger, mountain, peasWords ending with the letter “G”God, friend, plow, morgueWith the letter “G” in the middle of the wordGame, needle, sore throat, alcoholWords containing several letters “G”Gogol, aggregate, geology, dahliaCountriesGermany, Guinea, Greece, Georgia, Honduras. See all countries starting with the letter “G” Cities Gorlovka, Hamburg, Gelendzhik, Gomel, Grozny. See all cities starting with the letter “G”AnimalsGoose, pigeon, gazelle, cheetah, hyena, hippopotamus. See all animals starting with the letter “G” Vegetables, fruits and berries Pomegranate, pear, peas, mustard, grapefruit Professions Geneticist, geologist, guide, make-up artist, governess. See all professions starting with the letter “G” All names starting with the letter “G” with meanings and origins Male names Gennady, German, Gregory, Harry, Gavrila. See all male names starting with the letter “G”, as well as their meaning and origin. Female names Galina, Gulnaz, Greta, Gulnara. See all female names starting with the letter “G”, as well as their meaning and originModern tendencies

Under the influence of the “language of radio” and the requirements for “literate speech”, the fricative r is gradually dying out. Stunning in “x” at the end of words is dying out more slowly. In DARY there are zones with a plosive “g” and a stun in “x” (i.e. there used to be a fricative “g”), but there are no zones with a fricative “g” and a stun in “k” (i.e. there is no reverse process ). Hypercorrection: “GREEK WORK” (Larina, Ryazan), “gekaterina” (“Don’t be a fool, America”).

Only explosive g is distributed (there are many g/x, there is no <g>/k anywhere): DARIA 1-44

- 109,000 for "deneh", 447,000 for "denek" (including "denek", cf. 407,000 for "denki", 86,700 for "denki")

- 1,590 for “no money”, 4,050 for “no money”

- 619 for “many days”, 2,010 for “many days”

- 1,060 for “no money”, 860 for “no money”

- 118 for “a lot of days”, 1,550 for “a lot of money”

More Google:

- 951 for “snekh is coming”, 2010 for “snekh is coming”

- 345 for “white snack”, 161 for “white snack”

- 28 for “snekh falls”, 67 for “snekh falls”

And here, on the contrary, “k” is more often:

- 12,200 for “would you rather”, 3,640 for “would you please”

- 1,700 for “didn’t smoke”, 492 for “didn’t smoke”

- 328 for “not wet”, 705 for “not wet”

collapsed (AmoNik St. Petersburg)

Study Materials

Poetry

* * * G is a cheerful, kind gnome! There are many tales about him. He comes into the children's dreams at night and even during the day!

Poems about the letter "G"

Puzzles

* * * Goose, big, loud-mouthed goose - I’m a little afraid of him. The goose cackles: “Ge-ge-ge! Where is the goose? Under the letter...

Riddles about the letter "G"

Tongue Twisters

* * * Pear raised Grushenka. Pear gave her pears. The letter G will help Pear Pears to collect and eat.

Tongue twisters starting with the letter "G"

Fairy tales

Notes

- George Y. Shevelov “On the Chronology of h and the New g in Ukrainian” (Harvard Ukrainian Studies, vol 1. number 2 June 1977, p. 9) with reference to T. Skulina - Shevelov also has many examples of South East Slavic monuments XI century, although he dismisses this evidence

- Trubachev in comments to Vasmer

- V.V. Pokhlebkin. History of vodka (1991) p.62, link to Dictionary of the Russian Language of the 11th-17th centuries. - T.4. - M., 1977 - P.200

- From the book by B. A. Uspensky “History of the Russian literary language (XI-XVII centuries)” Moscow 2002

- V.V. Ivanov. Historical grammar of the Russian language - p. 108 - link to Shakhmatov

- TRADITIONAL CULTURE OF THE PEOPLES OF THE EUROPEAN NORTHEAST OF RUSSIA

- https://lingvoforum.net/index.php/topic,18745.msg759123.html#msg759123

- Vasmer

- Vasmer

- Wikipedia

- V.V. Ivanov. Historical grammar of the Russian language - p. 394

- M. V. Lomonosov. Russian grammar

- M. A. Tsyavlovsky